It was an otherwise ordinary day in 1386 when the citizens of Falaise, a town in Normandy, France, gathered to see justice visited upon a sow. The defendant was duly convicted of murder in a court of law for mauling a baby who died from the wounds. The pig was sentenced to be hanged in the town square. But before being strung up, in keeping with the Old Testament policy of “an eye for an eye,” the pig was made to suffer the same wounds it inflicted on the child: Its face was lacerated.

According to an account by Hampton L. Carson, published in 1917 in The Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, local farmers brought their own pigs along to watch the execution, presumably to deter them from committing similar crimes.

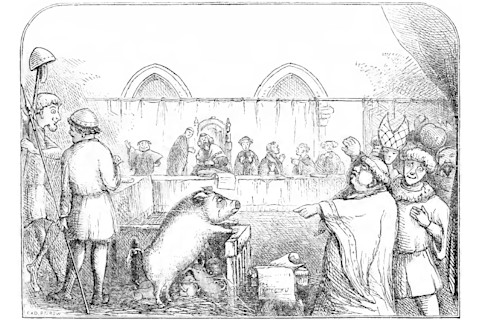

(Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons/Chambers Book of Days) Trial of a sow and pigs at Lavegny

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons/Chambers Book of Days

Justice for All

Trials of non-human animals have popped up throughout history and in many places in the world, but they seem to have been especially popular in medieval Europe. Though the animals most often hauled to the dock were pigs, plenty of others were, too, including roosters and rats, frogs and snakes, and even insects, such as grasshoppers and termites.

Lest you think these trials were nothing more than — ahem — kangaroo courts or vigilante justice, you should know that these animals were often represented by some of the best lawyers of the day. Carson describes how Bartholomew Chassenée, a major figure in French jurisprudence and legal philosophy, got his start defending rats. It was 1522, and the town of Autun had accused the local rats of destroying its barley crop. The rats were summoned to court, but to no one’s surprise, they failed to appear.

Read More: Why Do Black Cats Have A Reputation For Evil?

Chassenée argued before the court that, according to existing law, the accused could ignore a summons if compliance would pose undue risk. The town was brimming with cats, so the rats had no choice but to disregard the summons. Eventually, the case fell apart, and Chassenée went on to an illustrious career representing human clients.

Even when their legal counsel was not so clever, animal defendants were typically accorded all the legal rights and due process granted to humans. And at times, the animals prevailed. In a 2003 paper published in the journal Animal Law, Jen Girgen recounts how in 1713, a Franciscan monastery in Brazil was plagued with swarms of termites, helping themselves to the friars’ food, devouring the furniture and making a good start of bringing down the building.

The friars lodged a complaint with the bishop, and the insects were brought before a tribunal. The defense lawyer argued that the termites were God’s creatures and therefore entitled to food. The final verdict was a compromise: The friars were ordered to provide a habitat for the termites, and the termites were ordered to remain in that habitat. (Homeowners in the Deep South are eager to know if that plan worked, but Girgen doesn’t say.)

Of course, these were Franciscans, but Girgen cites other cases where courts gave animals leniency. In one case in 1519 in Stelvio, a village in the Alps, a judge banished an entire community of moles — but guaranteed them safe conduct (protection from cats and dogs) on their way out of town and allowed newborn moles and the pregnant members of the mole community more time to vacate.

Hard Questions on Legal Rights

It’s understandable that after seeing a baby mauled to death by a pig, the community would want some kind of closure. As strange as it seems now to haul a pig into court, it speaks well of the citizens of Falaise that they didn’t form a mob and take care of things extra-judicially. Of course, when medieval courts convicted animals, they were executed with as much brutality as their human counterparts were.

Animal trials are rare in modern times, though not unheard of. Dogs considered “vicious” or dangerous can be put to death, and sometimes their cases are heard by judges. However, modern canines are unlikely to benefit from excellent legal counsel and are generally not afforded the same rights as humans in similar situations. To do so would bring up some uncomfortable questions. If animals are entitled to a trial by jury and other legal rights when accused of a crime, are they not also entitled to other rights and protections, such as the right to life and liberty? If the sow could be hanged for killing a farmer’s child, what about the farmer who killed the sow’s piglets?

Read More: Why Dogs Sometimes Don’t Like Certain People

Whether questions such as these are viewed as a matter strictly of law or of morality, they teeter on the edge of a very slippery slope, and today’s conflicting views concerning animal rights make that edge not only more difficult to discern but that much more precarious.