Have you ever hesitated to treat yourself to a tuna steak or a colorful sushi plate because of concerns about mercury and other heavy metals? You’re not alone — and your caution is justified. Considered one of the top ten chemicals of public health concern by the World Health Organization, mercury can cause serious medical issues, distinctly for developing fetuses during pregnancy.

While eating fish regularly is encouraged for its nutritional benefits — especially during pregnancy — global industrial processes have dramatically increased heavy metal levels in our oceans. That means more mercury in the fish that end up on our plates.

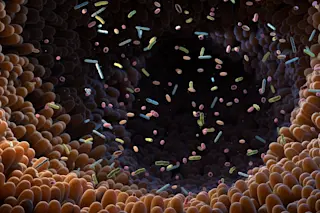

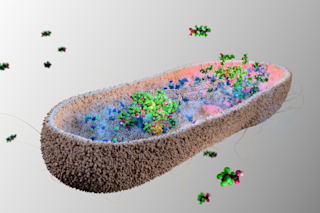

Scientists from UCLA and UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography may have come up with a clever solution. They’ve genetically modified a common human gut bacterium to help detoxify mercury before it can harm us. Their study, published in Cell Host & Microbe, lays the groundwork for ...