First mammograms are typically recommended at age 40. Colonoscopies are usually ordered when a person turns 45. In the future, a physician may remind a patient when it’s time to go for an MRI so their biological age can be calculated.

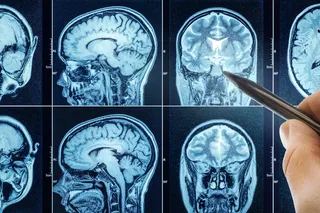

There’s a new algorithm that can take a single image from a brain MRI and produce a score indicating how the entire body is aging. The algorithm proved successful with participants in The Dunedin Study, a long-term study that began more than 50 years ago in New Zealand. Scientists are hopeful that it will one day become a routine part of preventive care.

Read More: Vital for Bone Health, Vitamin D May Also Slow Aging at the Cellular Level

Studying a Person's Health

When the Dunedin Study began in 1972, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was still years away from development, and researchers weren’t thinking about how they could one day use an algorithm to predict a person’s health outcomes.

At the time, scientists approached parents of more than 1,000 newborns and asked them to participate in a longitudinal study that would involve frequent follow-ups. Initially, the researchers examined how adversity and other environmental factors influenced the children’s development.

Over time, the longitudinal data from the Dunedin cohort complemented other research in progress. In 2003, for example, a study in JAMA Psychiatry found that the Dunedin participants with mental illness as adults also had a juvenile psychiatric history, which led to the recommendation of screening during adolescence. Similarly, the Dunedin data identified factors that lead to tooth loss. And as the cohort aged, their continued participation allowed researchers to track the impact of tobacco and cannabis use on lung function.

The most recent follow-up happened when the cohort turned 45. The participants underwent extensive testing, including a physical exam, cognitive assessments, blood work, and an MRI. Participants even stood for photos so a panel could later guess their age.

Researchers quickly realized that although the cohort members were all chronologically 45, some were much older and were aging at almost twice the rate. What did this mean?

Problematically, there was nothing the scientists could use as a point of comparison.

“It was a dead end of sorts,” says Ahmad Hariri, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University.

Quantifying Biological Age

Scientists needed a method that could quantify a person’s biological age in a way that considered their individual history. Hariri thought the solution might lie within brain scans. Ethan T. Whitman, a graduate student in Hariri’s lab, began working on an algorithm that could analyze a brain MRI and predict health outcomes for other organs. His work led to Dunedin Pace of Aging Calculated from NeuroImaging (AKA DunedinPACNI).

Using a sample MRI image from the Dunedin study, the program was able to analyze and measure different aspects of the participant’s brain structure. The data was crunched into a score that offered a point of comparison as to whether the participant was aging faster or slower than others in the study.

The research team was then able to reference the Dunedin data and question: did participants with a higher DunedinPACNI score also have a higher biological age?

Hariri says the results were stunning because they were immediately accurate and consistent. People with higher DunedinPACNI scores indeed had a higher biological age at their 45-year check-in. They had worse balance, moved slower and had weaker body strength. They reported more health issues and performed more poorly on the cognitive tests. Panelists who looked at their pictures even said they looked older.

DunedinPACNI is still undergoing validation tests, but the research team is confident that it could be used to predict a person’s likelihood of developing diseases such as heart disease, stroke, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

“If a person has a faster DunedinPACNI score, they are at significantly increased risk for developing dementia,” Hariri says.

The tool is free for clinicians, and because MRIs are becoming more common, Hariri says he hopes getting a biological age score calculated could one day become as common as a colonoscopy or mammogram. Perhaps one day, a person could open up their MyChart to view their DunedinPACNI score.

“If it’s outside the normal range, it would kickstart a number of decision processes for the physician and their patient. And if it’s lower, hey, good job. Keep up the good work,” Hariri says.

This article is not offering medical advice and should be used for informational purposes only.

Read More: Rate of Biological Aging Is Accelerating In Young People, Leading To Medical Issues

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

- Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit

- Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. The Dunedin study after half a century: reflections on the past, and course for the future

- JAMA Psychiatry. Prior Juvenile Diagnoses in Adults With Mental Disorders

- PubMed. Socio-economic and behavioural risk factors for tooth loss from age 18 to 26 among participants in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study

- PubMed. Differential Effects of Cannabis and Tobacco on Lung Function in Mid-Adult Life

- Nature Aging. DunedinPACNI estimates the longitudinal Pace of Aging from a single brain image to track health and disease