If you’ve ever struggled to keep up in spin class or wondered why sprint training feels extra brutal, you might be right to blame it on your genes — or more precisely, your ancient cousins’ genes.

A new study by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, and Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet has uncovered that some modern humans carry a Neanderthal genetic variant that hampers muscle performance.

Published in Nature Communications, the research suggests this ancient gene could halve a person’s chances of becoming an elite athlete.

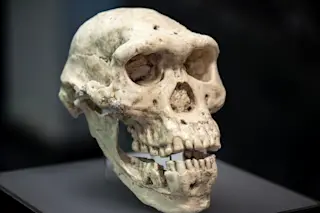

So, what exactly is this gene, and why does it matter for our bodies today? The research team has pinpointed a variant in the AMPD1 gene that some of us inherited from Neanderthals. Their findings show that all Neanderthals carried this specific variant, which is absent in other species.

AMPD1 is an important enzyme for ...