The tales we tell — from Homer and Genesis to your friend’s ninth recounting of that epic rave last summer — are rich with drug use. But studies show our ancestors were chewing, brewing and blazing long before they started to record their intoxicated escapades.

Virtually all human societies use mind-altering substances. What’s more, about 90 percent give drug-induced altered states of consciousness a role in their fundamental belief systems, according to a survey of 488 modern societies. And this isn’t new. Many psychoactive plants we consume today, and those that have fallen out of style, date back thousands of years.

A Psychoactive Sampling

Before we made drugs a societal menace, we respected them and used them for healing and spiritual purposes. Psychoactive plants fell under the jurisdiction of shamans, and some scholars believe early religion is rooted in their prophetic hallucinations, though this has been contested. Others wonder whether drugs played a part in the origins of symbolic life and major intellectual breakthroughs.

Use of Peyote, a desert cactus with natural hallucinogens, dates back as far as 5,700 years. It was so indispensable that some Native American groups traveled days or weeks each year to harvest a year’s worth of the holy cactus in the Chihuahuan desert of Mexico and Texas.

Peyote, a small spineless cactus, has been getting people high for thousands of years. (Credit: Shutterstock)

Shutterstock

In Fingerprints of God: The Search for the Science of Spirituality, religion correspondent Barbara Hagerty described a peyote ceremony: everyone “sat cross-legged on the floor, motionless, gazing at the flames with sleepy eyes dilated by the mescaline from the sacred herb peyote. Three strapping young men with long black hair moved around the circle, pounding on a water drum and singing an urgent chant.”

Other drugs have an even longer history. In the same region, another hallucinogen called the mescal bean, which was used in a similar way to peyote, has been found in caves and rock shelters extending back to 9,000 years ago. In Peru, the oldest remains of the psychoactive San Pedro cactus date to 6,800-6,200 B.C.

More familiar today is opium — its descendants are heroin and morphine — and it was equally renowned in the antiquity of the Old World. It produces euphoria, pain relief and drowsiness, and it seems to be the most widespread of the ancient drugs, reaching most of Europe by the sixth millennium B.C. Poppy capsules adorn many Eastern Mediterranean artifacts, like figurines and jewelry, highlighting opium’s range of symbolic meanings.

A figurine of the Poppy Goddess from Gazi, 1300-1200 B.C. (Credit: Pecold/Shutterstock)

Pecold/Shutterstock

In the South American Andes, coca is the drug of choice, and has perhaps been so for 8,000 years. Chewing the leaves of this plant, from which we now derive cocaine, helps to stave off fatigue, hunger, thirst and altitude sickness. Many indigenous tribes also use it in ritual contexts.

Smoking pipes in Argentina have been dated to as early as 2,100 B.C., and chemical analysis suggests they were used either to smoke tobacco or other hallucinogenic plants. As for marijuana, Neolithic Chinese farmers were growing hemp for various reasons by the fifth millennium B.C., including as a hallucinogen.

And of course, we can’t forget shrooms. Prehistoric Homo sapiens were so enamored of the fantastic fungi that many formed sacred cults around them in Mesoamerica. Small sculptures of human figures crowned with umbrella-like mushrooms are common throughout the region, dating between 500 B.C. and 900 A.D. In Siberia, Finno-Ugrian tribes have likely been aware of fly agaric — the classic image of a magic mushroom, red with white speckles — since “time immemorial.”

These mushroom stones were found at highland Mayan sites in Guatemala and are from around 500 B.C. Once thought as phallic stones, they’re now widely accepted as being associated with a mushroom cult. (Credit: Dr. Stephan F. de Borhegyi, 1961)

Origins of Craving

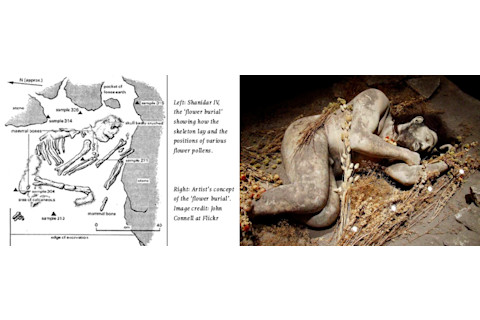

One of the oldest potential cases of medicinal drug use involves a 60,000-year-old Neanderthal. Around his burial site lay various plants, including the stimulant ephedra. Some have disputed this evidence, as the grave also contained the bones of a gerbil-like rodent that may have hauled in the plants itself.

Some wild animals have been observed to act inebriated after eating overly ripe fruit, and this points to one theory of the human-alcohol dynamic. It’s — magnificently — titled the “Drunken Monkey Hypothesis,” and it may account for our intoxication impulse.

Before they hunted for meat, our primate forebears foraged for fruit. The hypothesis suggests a strong desire for the smell and taste of alcohol, produced in fruit as yeast converts its sugars into ethanol, would help them to detect dinner at peak ripeness.

(Credit: Left, Stringer C. et al. 1994; Right, artist’s concept, John Cornell/Flicker)

In that evolutionary vein, some researchers speculate that mammals and psychoactive plants each influenced the development of the other over millions of years. They note that we have adapted to metabolize the plants, while their defense chemicals have evolved to replicate and disrupt the function of our neurotransmitters, implying a “deep time” relationship.

Intentional fermentation likely came after humans began using psychoactive plants, many of which are consumed raw. One of the first confirmed alcoholic beverages was a Chinese concoction of wild grapes, hawthorn fruit, rice and honey.

Considering that all staple cereals — like barley, wheat and maize — are fit for brewing, some have even suggested that humans may have domesticated these crops for beer rather than bread.

Wasn’t Always a War

Over the centuries humans learned to distill spirits and refine drugs like cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine. They experimented with snorting, injecting and inhaling their intense new creations. One theory of addiction is that psychoactive drugs weren’t as common or as addictive in our ancestral landscape, so we never evolved the internal control to resist them in high doses. Instead we relied on the limits of nature, and now we just aren’t wired to withstand their modern, purified abundance.

The increasing potency of drugs in an unrestricted environment has led to numerous epidemics throughout history, and today addiction is a global dilemma. As for the U.S., the opioid crisis in particular is growing more deadly each year.

More than 33,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses in 2015, and the next year about 64,000 died from drug overdoses in general. But the perception of drugs as a public enemy, and the push to eradicate them, seems to be a fairly new concept.

Elisa Guerra-Doce, a Spanish researcher, published a review of archaeological evidence for psychoactive drugs in prehistory. She and many others argue that despite contemporary problems, drugs have traditionally served socially constructive purposes. By examining the way humans have used them for millennia, we may gain a better understanding of how to benefit from them without the harm.

“Considering the failures of the war on drugs,” Guerra-Doce writes, “perhaps our modern societies should look into the past and learn something from ‘the primitive.’”