The urge to eat more than we need to can be powerful, even overwhelming, and it’s easy to blame ourselves for a lack of willpower. But what may seem at first glance like personal failure is really, in many ways, simply a physiological misfire — the body’s natural processes hijacked by a decidedly unnatural modern environment.

All of us overeat from time to time, and many do so on a regular basis. Obesity rates have soared over the past few decades and continue to rise, from 30 percent of adults in 2000 to more than 40 percent in 2020. That trend goes hand in hand with increased heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and various cancers, all driven in part by overconsumption of energy-dense foods.

This epidemic can, of course, be viewed as the product of a complex interplay of economic, social, and cultural factors. But those influences all converge at, and rely upon, a single point: human biology.

Why Do People Overeat?

From an evolutionary perspective, we overeat because our ancestors often had to endure famine. They couldn’t always predict their next meal, so when a feast came along they guzzled it down and stored the excess as body fat, to tide them over through times of scarcity.

That strategy made sense for people without a reliable food supply (it’s similar to animals gorging themselves before hibernation). But in this relatively new world of plenty, once we’ve consumed enough calories for short-term sustenance, our built-in tendency to keep eating does more harm than good.

In essence, our biology lags the progress we’ve made toward a safer, more comfortable world. As obesity experts Megha Poddar and Sean Wharton write, the current overeating epidemic is “the inevitable outcome of our primal instincts colliding with amazing, man-made abundance.”

Read More: The Rise Of The Obesity Epidemic

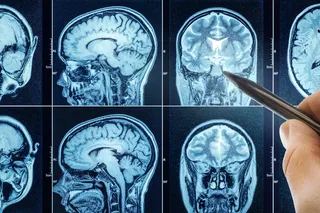

What Is the Brain’s Role in Overeating?

Food intake is regulated by the hypothalamus, a brain structure that coordinates many bodily processes to keep us in a stable state called homeostasis. Each time our stomachs are empty, the hypothalamus receives signals from the gut — via ghrelin, the famous “hunger hormone” — that stimulate appetite. Then, once we’re full, a wave of appetite-suppressing signals tells us to stop eating.

What Part of the Brain Controls Hunger?

In the longer term, the hypothalamus takes cues from an appetite-suppressant called leptin. Our leptin levels are directly related to the number of fat cells we have. As body fat increases, so does leptin, alerting the brain that the body has enough energy stored and induces feelings of fullness. But in some cases, the brain can become less sensitive to these signals. This condition, known as leptin resistance, often plays a role in overeating and obesity.

That may all sound simple enough, but it’s complicated immensely by the effects of the reward system: A network of brain regions that floods the body with pleasure-inducing chemicals like dopamine, opioids and cannabinoids when we eat. Long after we’re satiated, our bodies exploit this system to keep us operating on the more-is-better principle that evolution instilled in us.

Read More: A New Suspect in the Obesity Epidemic: Our Brains

How Does Mental Health Affect Overeating?

Despite its association with reward, overeating isn’t purely hedonistic. Often, we aren’t seeking pleasure for its own sake, but rather to counteract negative feelings like anxiety, boredom, and depression. James Greenblatt, chief medical director at Walden Behavioral Care, writes that a combination of appetite problems and mood disorders is “shockingly common.” According to one study, a whopping 80 percent of people with eating disorders have at least one other mental health diagnosis in their lifetimes.

Can Mood Affect Appetite?

Under optimal conditions — when we’re well-rested and emotionally stable — the brain’s frontal lobe could override the impulse to overeat. But if we’re tired or stressed, they’re much harder to resist, which is why binges often happen at night after a long day. Indeed, research has shown that cognitive dysfunction is a common factor in cases of chronic overeating.

However, we’re also prone to getting stuck in a feedback loop. David A. Kessler, former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, explains in his book The End of Obesity that extremely palatable foods change our brain circuitry in ways that drive us to pursue them even more. As he puts it, “Sugar, fat and salt makes us eat more sugar, fat and salt.” If left unchecked, this pattern can persist for a lifetime.

Read More: Forget Dieting. Here's What Really Works to Lose Weight

What Are the Genetics of Overeating?

In a sense, we’re all genetically predisposed to overeating, since we’re all descended from ancient humans who had to binge to survive. That evolutionary heritage left us with what is sometimes called a “thrifty genotype,” a set of DNA that turned us into well-oiled food-acquisition machines.

Still, most of us live in what health researchers deem an “obesogenic” environment (one that promotes weight gain and inhibits weight loss), but not everyone overeats to the point of obesity. That fact hints at differences in individual biology, determined by each person’s unique genetic code.

Is Obesity Genetic?

Though obesity can be caused by changes to a single gene in rare cases, it’s almost always the result of interactions between many genes (not to mention the environment in which their sum — a human being — exists). For this reason, a group of Finnish researchers noted in 2013, the genetic foundation of overeating and obesity is “notoriously difficult to disentangle.”

Is Obesity Hereditary?

But there’s no doubt obesity is passed down from parent to child. Studies comparing identical twins (who share the same DNA) and fraternal twins (who do not) suggest that 40 to 70 percent of variation in body size can be traced to genetics. More than 140 regions of the human genome have been linked to obesity, although differences in those genes only explain a small fraction of variation between people.

Advances in neurobiology and genetics have gone a long way toward explaining the intricate processes that control overeating. Yet, there’s still much left to learn, and researchers hope that as their understanding grows, they’ll be better equipped to help curb the global rise in obesity. As a team of researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, put it: “By elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying obesity alone can we rationally approach and effectively treat this devastating condition.”

Read More: Researchers Learn More About Complex Genetic Causes of Obesity