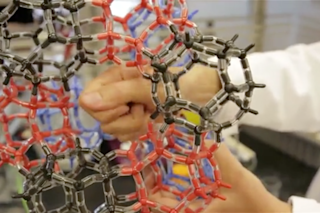

Senior author Omar Yaghi demonstrates how the MOF works using a model. A thin lattice of metals and organic compounds could turn moisture trapped in the atmosphere into drinkable water using only the power of the sun. By optimizing what they call a metal-organic framework (MOF) to hang on to water molecules, researchers at MIT and the University of California-Berkeley have created a system that passively catches water vapor and releases it later when exposed to heat from sunlight. Their device could offer a low-cost, sustainable means to deliver drinkable water to arid regions of the world. Their MOF is a tangled lattice of zirconium and fumarate, an organic compound. Such frameworks are composed of a dense knot of threads perfect for holding on to molecules. By altering the composition of the framework, MOF's can be optimized to grab different kinds of compounds — anything from hydrogen and methane to petrochemicals. There are thousands of such materials out there, and likely more still awaiting discovery. This particular porous framework was tuned to embrace water molecules, allowing it to sift H2O out of the air. Heating the material up with sunlight forces the water through a condenser, where it can be captured and put to use. In a paper published Thursday in Science, the researchers say that one kilogram of their material can produce 2.8 liters of water a day in conditions where the relative humidity is as low as 20 percent — about the same as most deserts. Although the material holds about 20 percent of its weight in water right now, they think they may be able to double its capacity with improved materials. The basic components are cheap and easy to acquire, they say, paving the way for large-scale production of the MOF. The key advantage of their material is the lack of any artificial power source. After all, we pull moisture out of the air with dehumidifiers, but they also suck up a good deal of electricity. Powering the device with sunlight bypasses that requirement, especially important in developing nations lacking infrastructure. Other devices that rely on a similar concept have been proposed, such as the Warka Water tower. Using designs borrowed from desert plants, the tower exploits temperature swings between day and night to capture water and funnel it to a tank. The MOF material operates in a similar way, but the porous mesh allows for more water to be held in a smaller area. To keep water flowing constantly, the researchers say that the system could soak up water overnight to disperse during the daytime, or it could be designed to force more air through, increasing the rate of water collection. The team is still tweaking both the design and the materials to coax more productivity out of the mesh.

New Material Sucks Drinking Water Out Of Thin Air

Discover how metal-organic framework MOF technology can generate drinkable water from air using only sunlight, improving water access sustainably.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe