doesn't have much oil, leaving the island nation heavily depended upon imports. What it does have, though, is natural gas—far under the sea in methane hydrate formations. The country said this week that it is going after those deposits, drilling test wells next year with the intention of beginning extraction before the decade is out.

Japan

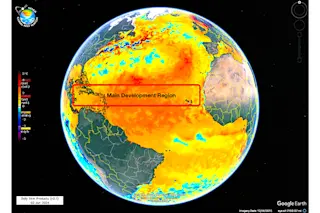

What makes methane hydrate unique is that it is a seemingly frozen and yet flammable material. Formed in cold, high-pressure environments, it is found throughout the world's oceans as well as under the frozen ground of countries with high latitudes. While global estimates vary considerably, the U.S. Department of Energy says, the energy content of methane occurring in hydrate form is "immense, possibly exceeding the combined energy content of all other known fossil fuels." [UPI]

No one has yet pursued hydrates in a major commercial way, so their enormous potential sits untapped. Japan succeeded ...