This summer is really the summer of the Moon. As we approach the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing, many people are thinking about our past and future relationship with our celestial partner. It is the only object in space whose surface can be seen with the naked eye (without going blind … sorry Sun), yet only two dozen people have even been there. As we look back at our first visit five decades ago, it’s worth taking a moment to consider just how unique Earth’s closest neighbor is.

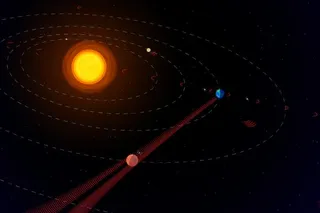

There are lots of moons in the solar system, so in that sense, the Moon is not unique. Some planets, like Jupiter and Saturn, have dozens upon dozens of moons that come in nearly every shape and size. In fact, every planet that has a moon of some kind has more than one … except Earth!

Earth’s moon isn’t the largest — not by a long shot. The largest planet boasts the largest moon as well, with Jupiter’s Ganymede coming in at over 5,200 kilometers in diameter. That’s a full ~67% larger than Mercury, the smallest planet. The Moon comes in at number 5 on the list of largest moons, between Io and Europa (two more of Jupiter’s moons). At 3,400 kilometers in diameter, the Moon’s is still larger than Mercury, though.

For the terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars), our Moon stands alone. Sure, Mars has two moons but Phobos and Deimos are glorified space potatoes, captured asteroids that zip around the planet. Our Moon is spherical and circles us at a relatively leisurely 27 days per orbit. It is also the only astronomical object other than the Sun that influences processes on Earth (think: tides … but not earthquakes or volcanic eruptions).

Even our moon’s birth sets it apart. A vast majority of the small chunks of rock and ice that orbit other planets were likely formed with the planet or captured by the planet’s gravitational well. Not our Moon. It was born of a cataclysm involving the early Earth. A massive collision with a Mars-size object jettisoned material off which coalesced into the current Earth-Moon system.

The Moon transiting in front of Earth on July 16, 2015, seen from DSCOVR. (Credit: NASA)

NASA

Speaking of which, now that Pluto is exiled to the land of dwarf planets, the Earth-Moon system is the closest we have to a twin planet in our solar system. The diameter of the Moon (~3,400 kilometers) is ~25 percent that of Earth’s (~12,700 kilometers) — a remarkably large ratio. Ganymede is only 6 percent the size of Jupiter.

The story of the Moon’s formation can also be seen by comparing the different densities of Earth and its partner. Grind up the Earth and measure the density of the material and you get ~5.5 grams per cubic centimeter. Do the same to the Moon and it’s only ~3.3 grams per cubic centimeter … which is actually pretty close to the density of the upper layers of Earth. This likely means that the Moon was made up of the outer parts of proto-Earth (crust and mantle) after the collision and not the heavy metallic innards.

Some of this turbulent history is visible on the surface of the Moon as well. Unlike the other big moons like Ganymede, Titan, Europa, Callisto and Triton, our Moon lacks any real atmosphere and isn’t covered in ice. Sure, it is a lot closer to the Sun, so maybe it lost much of its ice (there is some), but it is a much more desolate locale compared to the icy moons of the solar system.

That being said, there are some definite advantages to going back to our planetary companion.v The Moon is only around 240,000 miles (348,000 kilometers) from Earth (on average), yet we’ve only been there 6 times. If we need a springboard to get out to the rest of the solar system, it is likely going to take getting back to the Moon and getting comfortable living down our celestial street, so to speak. There is a lot we don’t know about the Moon and its history, so let’s use this anniversary to get back into the mindset of voyage and discovery across the solar system.

Correction 6/18/19: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the diameter of the Earth and the ratio of its diameter to the Moon’s. We regret the error. Apparently I can’t remember to convert miles to kilometers before I do my math.