This article was originally published on Sept. 21, 2022.

For centuries, scholars looked at ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and scratched their heads. Scholars had no idea what the various symbols signified and the ancient texts were a mystery.

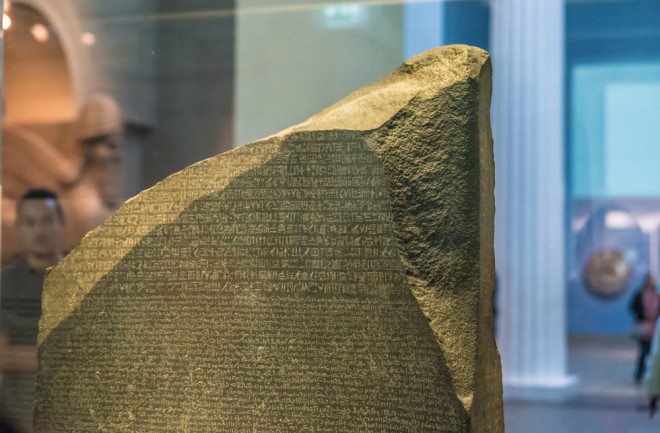

That all changed in 1799 when a large stone was uncovered in Rosetta (now el-Rashid), a port city on the Nile river. The stone was inscribed in three languages — Egyptian hieroglyphics, Egyptian demotic (a form of shorthand for hieroglyphics) and ancient Greek.

Scholars knew ancient Greek, and although it took them several decades, the inscription taught them how to read hieroglyphics. Dubbed “The Rosetta Stone,” this large rock unlocked insight into thousands of years of ancient texts.

Deciphering Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphics

The Rosetta Stone was about 4 feet tall and it had plenty of room for inscription. The top part had 14 lines written in hieroglyphics. The ancient Egyptians believed hieroglyphics was the written language of the Gods, and the text was typically only understood by the more educated members of the priesthood.

The middle part of the stone contained 32 lines in demotic. To the people who discovered the stone, demotic looked like a series of squiggles and loops. To the ancient Egyptians, it was a form of shorthand for hieroglyphics and it was used for daily affairs. It most likely resembled the language that Egyptians used every day.

The bottom part of the text was 53 lines written in ancient Greek. The Rosetta Stone was likely inscribed around 196 B.C. when the Ptolemies ruled, who were Hellenic and although they kept hieroglyphics, they preferred Greek.

Read More About the Rosetta Stone:

The Rosetta Stone is 2,200 years old.

The stone affirms the divine cult of King Ptolemy V on the first anniversary of his coronation.

The stone weighs 1,680 pounds.

Many scholars in the early 1800s knew how to read ancient Greek, and understood quickly the purpose of the stone.

The stone, according to the Greek inscription, was a decree. It was to be copied with the three languages and placed in every temple of significance throughout Egypt. That meant the demotic and hieroglyphic portions would be similar to the Greek text, and for the first time ever, scholars had a shot at understanding the mysterious symbols.

Cracking the Code of Rosetta Stone Hieroglyphics

By 1802, scholars could deduce the meaning of the Greek text. But translating the rest of the stone was a slow, puzzle-piecing process. Multiple scholars worked independently on deciphering the text, and their collective findings worked toward a final solution. One scholar, for example, identified the hieroglyphic symbol for Queen Cleopatra. Another scholar recognized how a specific symbol always appeared before the name of a goddess, princess or queen.

For the next decade, scholars worked to crack the code, and by the early 1820s, some claimed they could read hieroglyphics. They learned there could be multiple meanings to the symbols. In some instances, the symbol of a lion represented the animal. On other occasions, the lion represented a letter. This would be akin to using a snake to represent the letter ‘S’ or an open hand to represent the letter ‘D.’

The Rosetta Stone enabled scholars to read hieroglyphics more than a millennium after the language ceased to be spoken or written. It’s likely that the Egyptian language faded sometime between the seventh and ninth centuries and Egyptians have spoken Arabic since the Middle Ages. One historian has called the stone “revolutionary” because it opened up letters, stories, documents, and inscriptions that had puzzled scholars for centuries.

Read more: The 6 Most Iconic Ancient Artifacts That Continue to Captivate

The Rosetta Stone Discovery and the Quest to Return a Relic

Although the Rosetta Stone is Egyptian, it has not been in the country for more than 200 years.

The Rosetta Stone was found by members of a French military unit who were occupying Rashid, which they called Rosetta.

The French quickly lost military campaigns to their archnemesis, the British, and then lost the stone in a treaty of capitulation. It was whisked away to England.

The Rosetta Stone is on display at the British Museum in London. Egyptian authorities have made it clear they would like the stone returned to its homeland. The stone, however, is the most visited item in the British Museum, and the curators loathe to give it up.

Supporters of returning the stone to Egypt argue that not only does it belong to the country — including the importance of Rosetta Stone to ancient Egypt — but it was also likely uncovered by an Egyptian. The Rosetta Stone discovery happened when the French military was in Rashid and a unit was ordered to fortify a fort. They reused stones from a crumbling building, and the Rosetta Stone was among the rubble. At some point, it had been used as building material.

The French military officer overseeing the fortification was unlikely to have been doing the heavy lifting. The stone was likely discovered by an unnamed Egyptian laborer who called it to the officer’s attention, who then took credit for himself.

Although the laborer’s name was lost to history, his discovery meant that 30 centuries of Egyptian history was found.