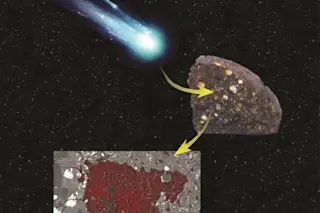

The cometary fragment was preserved inside an asteroid and transported to Earth in a meteorite. (Credit: Larry Nittler/NASA) Our solar system is a whopping 4.5 billion years old. And those earliest days were some of the most interesting for astronomers. That's when the planets formed, building from dust grains into the whole worlds that now populate our space neighborhood. But most of this material has been drastically changed since its early days – incorporated into planets, or baked by the sun and weathered by time. However, if we could find material that hasn’t been changed in some way it would help astronomers understand what the early solar system looked like. And sometimes, just rarely, such prizes rain from the heavens.

In 2002, researchers with the U.S. Antarctic Search for Meteorites program were exploring Antarctica's LaPaz Icefield when they came across an unusual space rock. The meteorite itself was valuable, belonging ...