Key Takeaways on Who Discovered the World Is Round

- Aristotle, working in Athens in the 4th century B.C., discovered that the world is round.

- Aristotle first discovered that during solar eclipses, Earth’s shadow always appeared on the Moon’s surface as a circle. He realized that only one object would invariably cast its shade in that shape: a sphere. And second, different stars and constellations are visible from different latitudes. If Earth were flat, everyone everywhere would be looking up at the same sky.

- By the late Middle Ages much of humanity was on the same page about Earth’s shape.

Almost any way you look at it, Earth’s surface appears flat. The average adult, standing on an expanse of perfectly level ground, can see just 3 miles to the horizon — not nearly far enough to observe the curvature directly. Even the summit of Mt. Everest doesn’t offer sufficient vantage.

To fully appreciate Earth’s arc with your own eyes, you must view it from at least 35,000 feet above sea level, an altitude only accessible by plane. In other words, no human living before the 20th century had first-hand experience of our planet’s true shape.

Yet nearly all educated people today recognize this apparent flatness as an illusion. We have a single man to thank for that: the Greek philosopher Aristotle, working in Athens in the 4th century B.C. According to historian James Hannam, author of The Globe: How the Earth Became Round, Aristotle was the first and only person to deduce that, contrary to all common sense, the ground beneath his feet curved imperceptibly.

His discovery then spread, gradually, around the world. “It took over 2,000 years to happen,” Hannam says, “but ultimately everyone from China to America knows the Earth is a globe.”

Who Discovered the World Is Round?

Intuitive as the flat-Earth model seems, it poses obvious problems. For example, if Earth were flat, ships would simply become smaller and smaller as they sailed away from shore; instead they disappear below the waves when they cross the horizon. And why doesn’t the ocean cascade over Earth’s outer rim? Conundrums like these left Aristotle second-guessing what his eyes told him.

As he marshalled evidence for sphericity, two astronomical observations proved especially compelling.

Read More: Why Does Everything Look Flat Even Though the Earth Is Round?

Which Discovery Proved the Earth Is Round?

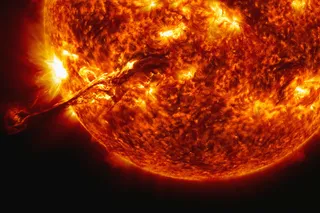

First, during solar eclipses, Earth’s shadow always appeared on the Moon’s surface as a circle. Aristotle realized that only one object would invariably cast its shade in that shape: a sphere. (An earlier philosopher named Anaxagoras had worked out a system in which these shadows could be explained by Earth being a flat disk that always faced the moon straight on, but of course we now know it rotates.)

Second, different stars and constellations are visible from different latitudes. If Earth were flat, everyone everywhere would be looking up at the same sky — instead, each of us sees only the part that isn’t obscured by the globe’s curvature.

This logic quickly persuaded Mediterranean society, but news diffused slowly across the rest of the ancient world.

The Spreading of Aristotle’s Ideas

The Romans disseminated Aristotle’s ideas as far afield as India, which then transferred them to Islamic philosophers in the 8th century C.E. Western Europe lost sight of science through much of the medieval period, but the English monk Bede reintroduced the concept of a spherical Earth to Christendom around 725.

“If all things are included in the outline,” he wrote, “the Earth's circumference will represent the figure of a perfect globe.”

There were holdouts — China, for example, with its traditional cosmology centered on a square Earth, persecuted Jesuit missionaries who taught otherwise in the 1600s.

“It was very late in history that you could safely say everybody in the world is being brought up to believe Earth is a globe,” Hannam says. “Until well into the 20th century.”

Nevertheless, by the late Middle Ages much of humanity was on the same page about Earth’s shape. For Europe in particular, it wasn’t even a matter of controversy. Long before the Magellan-Elcano expedition completed its circumnavigation of the globe in 1522, no one doubted that, in theory, circumnavigation was possible.

It’s a common misconception that Christopher Columbus, when he set sail for the East Indies, sought to prove Earth was round — in fact, he took it for granted. Neither he nor any other educated European feared that the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria would plunge off the edge into space. That was merely a legend, invented centuries later by the American writer Washington Iving.

Read More: 38 Famous Scientists Who Changed the World Through Their Discoveries

The First Scientific Theory

Earth’s surface has now been explored and mapped more or less exhaustively and even photographed from space in all its spherical grandeur. We have far more reasons than we need to accept the roundness of our cosmic home. But it wasn’t always that way.

“Everybody once upon a time thought the Earth was flat,” Hannam says. “The reason they thought that is, it’s blooming obvious.”

But then a skeptic came along. Refusing to be taken in by his senses, Aristotle turned to the burgeoning methods of science, not unlike a modern astronomer or geographer. In place of conventional wisdom, he substituted careful observation and rational argument.

In Hannam’s opinion, his well-reasoned case in support of a round Earth “makes it the first really important scientific theory.”

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: