In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, written in 1609, Ophelia marches to her watery grave wearing a garland of flowers: crow-flowers, nettles, daisies and long purples. To the modern reader, this is mere description. But to a Victorian reader with a particular education, it could be much more.

The crow-flower was known as the “Fayre Mayde of France” at the time; long purples were likened to dead men’s hands or fingers; the daisy signified pure virginity; and nettles had the peculiarly specific meaning of being “stung to the quick,” or deeply and emotionally hurt.

In Louise Cortambert’s The Language of Flowers, adapted from a French book and first published in London in 1819, she offers a translation of the arrangement. For one, each of these flowers grow wild, “denoting the bewildered state of beautiful Ophelia’s faculties.” Together with the right arrangement, the flowers can be read as their own sentence: “A fair maid stung to the quick; her virgin bloom under the cold hand of death.”

But as British social anthropologist Jack Goody notes in his own book, The Culture of Flowers, the history of this symbolic language of flowers — called floriography — is murky. Its more modern emergence, particularly in a series of what are essentially vocabulary books published in the 19th century, spark one question: Was this the discovery or the invention of tradition?

Planting Seeds

Early French literature from the 17th century made symbolic use of flowers and, as Goody argues, this practice was spurred on by a variety of other factors. Expanding trade with the East brought a whole host of exotic flowers to Europe, a rapidly expanding retail market increased the consumer base for flowers, a developing interest in the field of botany boosted demand for flowers, and widespread access to education — particularly in France — set the stage for a new floral lexicon.

Read More: How Flowering Plants Conquered the World

But it was the letters of English writer Lady Mary Wortly Montagu, written while she lived in Turkey from 1716 to 1718, that seeded the idea of a codified language of flowers in England. In Eastern Europe and Asia, the blossoms boasted a rich communicative history as well. Lady Mary wrote of a codified Turkish language of objects, usually arranged by rhyme: “Tel — Bou ghed je gel,” translated as “Bread — I want to kiss your hand.”

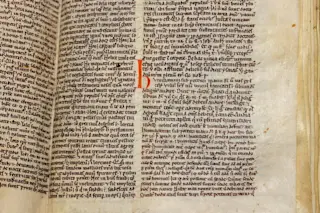

Later on, other guidebooks joined Cortambert’s The Language of Flowers. Henry Adams published his Language and poetry of flowers in 1844. The floral kingdom: Its history, sentiment and poetry by George Daniels came out in 1891. Kate Greenaway’s The language of flowers was first printed in 1884, then reprinted in 1992 and 2013. And Catherine Klein published The language of flowers in Boston in 1900, around the latter end of the Victorian era.

These lists were, in a word, extensive. In Anna Christian Burke’s The Illustrated Language of Flowers, published in 1856, the flowers are organized alphabetically. Yet there are 49 entries for the letter ‘A’ alone. Yellow acacias supposedly spoke of secret love; aconite (or wolfsbane) was a messenger of misanthropy; the common almond suggested stupidity and indiscretion, while the flowering almond was a symbol of hope and the laurel almond a symbol of treachery.

This could form a bizarre form of communication for those in the know. Consider a Victorian lady mailing out a bundle of asphodel, which in this language means her “regrets follow you to the grave.” Sent to a grieving friend, this would likely be interpreted as a message of support. Sent to an ex-lover, it could mean something else entirely — depending on what else is in the bouquet. Add a bay leaf, which means “I change but in death,” and it becomes a statement of undying love. Add a belvedere, which spells out “I declare against you,” and perhaps the regret is that this ex-lover has lived so long.

Something Old, Something New

This language of flowers went on to inform the art and writing of later periods, according to Goody, particularly in the realms of French poetry and Impressionist painting. But the language, while having ties to traditional knowledge both in France (where it was most enthusiastically formalized) and in Eastern Europe and Asia, was not exactly a tradition rediscovered.

“In fact, the opposite is nearer the truth: we are in the presence of a deliberately created addition to cultural artefacts, a piece of initially almost fictive ethnography which takes on an existence of its own as a product of the written rather than the oral,” Goody writes. Many of the guidebooks purported to explain a language forgotten by the reader, but known to their mother or grandmother.

Cortambert's book described the traditions of the Turkish people and the flower traditions of India, but contrasted them with European traditions — particularly in the realm of literature and chivalry, when the giving of favors and use of flower imagery was widespread. In this sense, she, along with her contemporaries, seemed to mean no deception when they spoke of reviving Europe’s tradition of a floral language.

Indeed, flowers have been used in many places to mean many things, including throughout Europe. It was in this way that a Victorian language of flowers was an invention of sorts: The fixed, formal meanings attached to them simply didn’t exist before.

It seems as though even the earliest authors on the language struggled with this. As Burke notes: “The meaning attached to flowers, to have any utility, should be as firmly fixed as possible; no licence whatsoever has therefore been taken in creating or changing meanings. The Editor has simply confined herself to the task of making the best selection she could from the different sources of information at her disposal …”