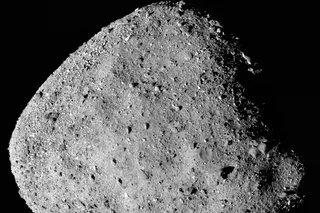

This animation comprises 101 images acquired by the Navigation Camera on the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft as it approached comet 67P/C-G. The first image was taken on August 1, 2014, and the last on August 6 at a distance of 110 kilometers, or 68 miles. (Source: ESA/Rosetta/Navcam) It took five loops around the Sun, three gravity-assist fly-bys of Earth and one of Mars, and a journey of 3.97 billion miles lasting 10 years, five months and four days. After all that, the Rosetta spacecraft finally reached it destination today — and made history. Rosetta is the first spacecraft ever to rendezvous with a comet. It is now in quasi-orbit (more about that in a minute) around comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. For more than a year, it will take pictures and gather data, and it will also send a lander down to the surface, all in a quest to help us understand ...

Rosetta Has Arrived, and the View is Astounding

Discover comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko through stunning images captured by the Rosetta spacecraft. Join the journey of exploration!

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe