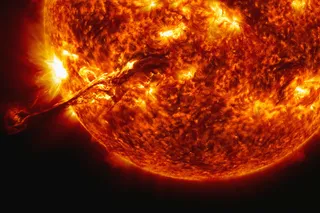

America's current plans for human space exploration seem horribly slow, considering we won't leave Earth's orbit until 2025 and won't reach Mars until 2035. Worse than that, solar radiation spikes could keep us grounded for decades more. The Sun emits a steady stream of potentially deadly cosmic radiation. As long as humans remain within the Earth's atmosphere, the threat posed by this radiation is practically nil, but any extended trips into deep space require careful shielding to protect astronauts from the threat of radiation sickness or cancer. The exact levels of radiation vary depending on the severity of solar activity, which falls into a number of predictable cycles. That's where the problem starts, according to a new study by NASA scientist John Norbury. We already know about the Schwabe cycle, which shows sunspot activity reaches its peak, known as the solar maximum, every 11 years. When this occurs, there's a big increase in solar flares and coronal mass ejections, which together spread deadly radiation throughout the solar system. The last solar maximum was reached in 2002, so we're headed for more in 2013, 2024, and 2035. Those last two dates are worrying, considering the current "2025 out of orbit/2035 to Mars" plans of the United States. Of course, if solar flares really are a problem, then it's easy enough to adjust the years slightly to avoid them. But we might be dealing with an even bigger problem: there's also the Gleissberg cycle, which is a longer cycle where the intensity of the solar maximums themselves wax and wane over a period of about 80 to 90 years. That means all flares would be significantly more deadly, the radiation would be greater, and any trips beyond Earth's orbit incredibly, perhaps impossibly, dangerous. So when is the next time we hit the peak of the Gleissberg cycle? That's the problem: we don't know, at least not exactly. In order to know the exact timing of the next Gleissberg maximum, we would have to know when the last ones occurred, and that would require sunspot records going back centuries, which is something we don't have. However, there are some indirect ways to estimate when the previous maximums occurred, mostly involving carbon-14. Scientists are fairly sure the last maximums were in 1790, 1870, and 1950. That seems to put the next Gleissberg maximum at right around 2030, with a total danger zone of about 20 years from 2020 to 2040. That's precisely when the United States---not to mention China and other countries---hope to send astronauts back to the Moon and onto Mars. If radiation levels are lethally high, a Mars mission could be a horrific failure, as astrobiologist Lewis Dartnell explains:

"The worse-case scenario is that if you radiate a crew sufficiently, they'd all succumb to radiation sickness within a few days and essentially vomit and diarrhoea themselves to death within an enclosed capsule."

If all these fears of increased radiation come to pass, it still might be possible to send astronauts to Mars, assuming radiation shielding can be suitably improved. But that's going to take serious investment in new technologies that can repel the cosmic rays without creating secondary radiation. Honestly, it might just be easier to get to Mars by the end of the decade. Hey, it worked for the Apollo project... [Advances in Space Research via Physics World]

io9. Escape to the world of tomorrow.

This post originally appeared on io9.