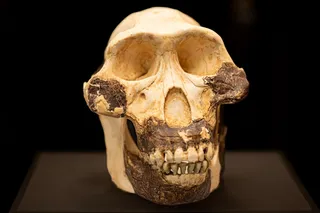

Millions of years ago, our ancient ancestors transitioned from the forests to the grasslands of Africa, where their need for new food sources led to their consumption of grasses.

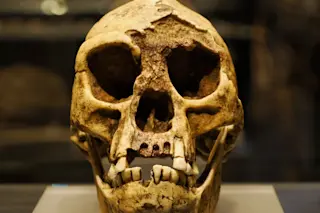

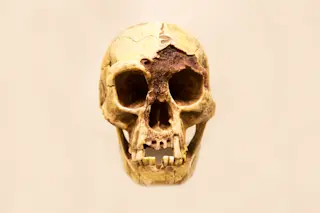

But recent research suggests that the hominins learned to love these plants, including their grains and their underground organs, thousands of years before their teeth had transformed to eat them effectively. In fact, it took a long time for the hominins’ tastes and teeth to align, with their molars evolving over time, shrinking and stretching, to make munching through tough grassy plants easier.

Reported in Science, the results reveal that behavioral adaptations have prompted physical adaptations in hominins through the evolutionary process of “behavioral drive.” This means that the hominins were able to adapt to their new environment through the transformation of their diet before the transformation of their teeth — an ability that could have contributed to their success.

“We ...