Paleontologists devote their lives to the study of the past, looking for connections that explain how we arrived at the world around us today. It’s fitting, then, that some paleontologists are examining the origins of their discipline’s modern landscape. These scientists are addressing the wooly mammoth in the room: that colonialism still dramatically shapes paleontological research and collaboration, long after the so-called Age of Empire.

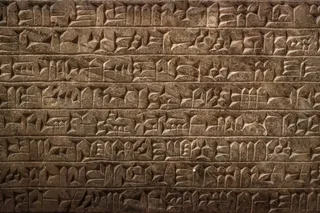

While people around the world have studied nature, including fossils, for thousands of years, the modern disciplines of natural history and paleontology were born in the last several hundred. Colonial voyagers traveled the world, documenting and, in many cases, extracting plants, animals and fossils that they felt could be of economic and scholarly benefit. These expeditions set the course for today’s science, and specimens collected then still are used by modern researchers to understand concepts like climate change and habitat destruction. But the colonial mindset ...