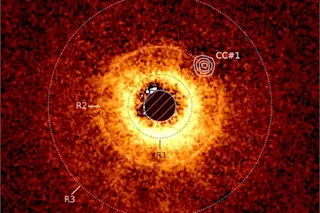

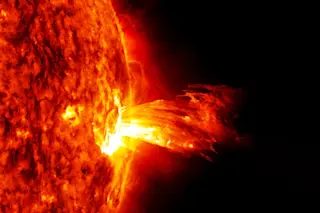

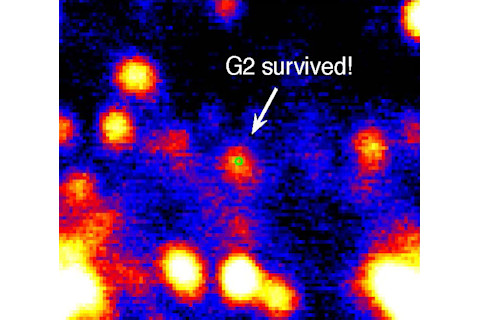

Earlier this year, astronomers watched as an object named G2 zoomed through space and passed close to the black hole at the center of our galaxy. Many thought G2 was a cloud of hydrogen gas that the black hole would rip apart and devour, unleashing fireworks we could see through telescopes on Earth. But they were wrong on both counts: G2 isn’t a gas cloud, and, like a rainy Fourth of July, the fireworks never happened. That may sound disappointing, but it’s a story of mistaken identity and a journey to the center of the galaxy—and how could that be disappointing? A research team led by Andrea Ghez of UCLA has said for more than a year that G2 is not just a cloud of gas: It’s a cloud of gas enveloping a secret star. The team also calculated that this mystery object would come closest to the black hole this summer, a few months later than other groups thought. They stood at the ready at the ultrasensitive Keck Observatory to watch. But nothing happened. Yesterday, her team announced that G2 had held itself together. It emerged relatively intact from its black-hole encounter, which is why telescopes saw no explosions in the sky. But a gas cloud alone couldn’t have withstood that kind of gravitational grappling. It would need to have something denser inside: a star, just like they’d said.

Two Become One

But that’s not the full story. The researchers’ new analysis shows G2 is actually a pair of stars that once peacefully orbited each other. The black hole disturbed their calm companionship, sending them spiraling into each other. They are in the process of merging into one star: a star two times as massive as the sun, and 30 times as luminous. The other stars near the galactic center (whose population is packed like Tokyo’s compared to our Wyoming-dense part of the galaxy) heat up the gas at G2’s surface, shrouding the system in gas and dust. This cloak of mystery is what disguised G2’s true nature and led to premature firework announcements.

Stellar Collisions

Ominously, the team concludes that “G2 is not alone.” There are thousands of stars in the neighborhood of the supermassive black hole. And stars like the ones that morphed into G2 usually come in pairs. Gravitational disturbance from the black hole may often cause these couples to crash violently into each other, become one unit, and then lose their separate identities. It’s the celestial version of marriage gone awry. And like a marriage, the G2 drama happened within a human lifetime. Astronomical events that begin and wrap up in a few years are rare. (Neil deGrasse Tyson didn’t pull out the “cosmic calendar” for no reason.) Historically, astronomers take snapshots of celestial bodies, catching them at some particular point in their development, which future generations of astronomers can return to decades or centuries later. A large part of G2’s dramatic appeal was that it played out quickly, and astronomers finally had the tools to see it happen in real-time. G2’s newly-confirmed stellar identity doesn’t change this fact. With powerful telescopes, and our lucky proximity to a black hole, Ghez says, “we are seeing phenomena about black holes that you can’t watch anywhere else in the universe.” With luck, many more such phenomena will lie ahead—even if there’s no fireworks.