In Jeffrey Bada’s laboratory at the University of California, San Diego, there’s a cardboard box containing the earliest evidence of how life began on Earth. The box holds hundreds of tiny vials filled with grimy, brown residues collected in the early 1950s by a University of Chicago graduate student named Stanley Miller. Each vial is marked with a page number corresponding to a notebook where Miller recorded an experiment undertaken with his adviser, the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Harold Urey.

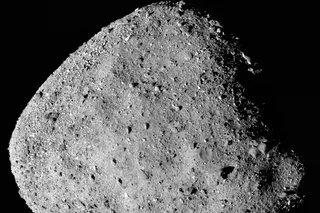

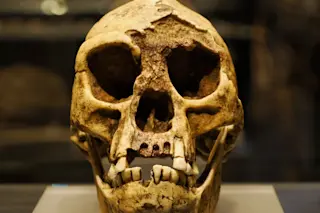

Their goal was to synthesize amino acids — the building blocks of life — as they might have been created on early Earth. The results launched a hunt for life’s origins that’s now uncovering these building blocks in surprising places, like the surface of comets and in deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

The modern origin question has bedeviled scientists since Charles Darwin proposed his theory of evolution in the 19th century. If all ...