Viktor Sarianidi, barefoot at dawn, surveys the treeless landscape from a battered lawn chair in the Kara-Kum desert of Turkmenistan. "The mornings here are beautiful," he says, gesturing regally with his cane, his white hair wild from sleep. "No wife, no children, just the silence, God, and the ruins."

Where others see only sand and scrub, Sarianidi has turned up the remnants of a wealthy town protected by high walls and battlements. This barren place, a site called Gonur, was once the heart of a vast archipelago of settlements that stretched across 1,000 square miles of Central Asian plains. Although unknown to most Western scholars, this ancient civilization dates back 4,000 years—to the time when the first great societies along the Nile, Tigris-Euphrates, Indus, and Yellow rivers were flourishing.

Thousands of people lived in towns like Gonur with carefully designed streets, drains, temples, and homes. To water their orchards and fields, they dug lengthy canals to channel glacier-fed rivers that were impervious to drought. They traded with distant cities for ivory, gold, and silver, creating what may have been the first commercial link between the East and the West. They buried their dead in elaborate graves filled with fine jewelry, wheeled carts, and animal sacrifices. Then, within a few centuries, they vanished.

News of this lost civilization began leaking out in the 1970s, when archaeologists came to dig in the southern reaches of the Soviet Union and in Afghanistan. Their findings, which were published only in obscure Russian-language journals, described a culture with the tongue-twisting name Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. Bactria is the old Greek name for northern Afghanistan and the northeast corner of Iran, while Margiana is further north, in what is today Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Through the region runs the Amu Dar'ya River, which was known in Greek history as the Oxus River. Western scholars subsequently used that landmark to dub the newly found culture the Oxus civilization.

The initial trickle of information dried up in 1979 when the revolution in Iran and war in Afghanistan locked away the southern half of the Oxus. Later, with the 1990 fall of the Soviet Union, many Russian archaeologists withdrew from Central Asia. Undeterred, Sarianidi and a handful of other archaeologists soldiered on, unearthing additional elaborate structures and artifacts. Because of what they have found, scholars can no longer regard ancient Central Asia as a wasteland notable primarily as the origin of nomads like Genghis Khan. In Sarianidi's view, this harsh land of desert, marsh, and steppe may instead have served as a center in a broad, early trading network, the hub of a wheel connecting goods, ideas, and technologies among the earliest of urban peoples.

Harvard University archaeologist Carl Lamberg-Karlovsky believes the excavation at Gonur is "a major event of the late 20th century," adding that Sarianidi deserves credit for discovering the lost Oxus culture and for his "30 consecutive years of indefatigable excavations." To some other researchers, however, Sarianidi seems more desert eccentric than dispassionate scholar. For starters, his techniques strike many colleagues as brutish and old-fashioned. These days Western archaeologists typically unearth sites with dental instruments and mesh screens, meticulously sifting soil for traces of pollen, seeds, and ceramics. Sarianidi uses bulldozers to expose old foundations, largely ignores botanical finds, and publishes few details on layers, ceramics, and other mainstays of modern archaeology.

His abrasive personality hasn't helped his cause, either. "Everyone opposes me because I alone have found these artifacts," he thunders during a midday break. "No one believed anyone lived here until I came!" He bangs the table with his cane for emphasis.

Sarianidi is accustomed to the role of outsider. As a Greek growing up in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, under Stalinist rule, he was denied training in law and turned to history instead. Ultimately, it proved too full of groupthink for his taste, so he opted for archaeology. "It was more free because it was more ancient," he says. During the 1950s he drifted, spending seasons between digs unemployed. He refused to join the Communist Party, despite the ways it might have helped his career. Eventually, in 1959, his skill and tenacity earned him a coveted position at the Institute of Archaeology in Moscow, but it was years before he was allowed to direct a dig.

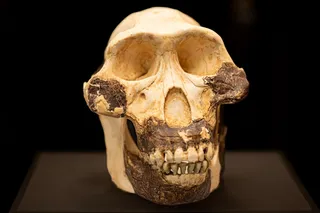

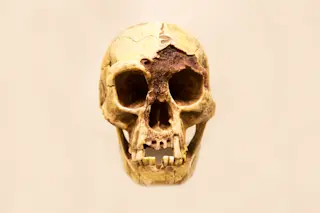

When he finally received permission to run his own excavations, Sarianidi worked in northern Afghanistan during the relatively peaceful decades of the 1960s and 1970s. His most famous discovery there came just before the Soviet invasion in 1979. His team uncovered an astounding hoard of gold jewelry in the graves of Bactrian nomads who lived around the first century A.D. But the region's mysterious Bronze Age sites, dating to the second and third millennia B.C., intrigued Sarianidi more. His excavations revealed thick-walled structures built with regular proportions and a distinctive style of art. Most scholars had thought that such sophisticated settlements had not taken root in the region until more than 1,000 years later.

Sarianidi had long suspected that similar sites might be found beneath a collection of strange mounds he had glimpsed during a 1950s trip in the Kara-Kum desert, a barren region in the middle of eastern Turkmenistan. Later, during a brief visit to a colleague's dig in that area in the mid-1970s, he commandeered a car and driver to investigate the site more closely. It was June, he recalled, and the heat was so overpowering he had to overcome an urge to turn back. Then, not far from the rough road, he spotted mounds rising up from the plain.

In treeless areas, such geographic features often indicate ancient settlements formed from mud-brick structures that later human occupation has compressed over time into artificial hills. The site covered so much land that Sarianidi assumed it dated from medieval times. So he was astonished to find pottery resembling what he had found in ancient Bactria.

When the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan forced him and other archaeologists to relocate to other areas of interest, Sarianidi remembered this site, which locals call Gonur, and determined to return. In the early 1980s, he came back to Turkmenistan, working at Gonur and other sites.

What he has uncovered at Gonur is a central citadel—nearly 350 by 600 feet—surrounded by a high wall and towers, set within another vast wall with square bastions, which in turn is surrounded by an oval wall enclosing large water basins and many buildings. Canals from the Murgab River, which once flowed nearby, provided water for drinking and irrigation. The scale and organization of this construction was unmatched in Central Asia until the Persians' arrival in the sixth century B.C.

Sarianidi's team has also turned up intricate jewelry incorporating gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and carnelian. The prowess of the Oxus metalworkers—who used tin alloys and delicate combinations of gold and silver—were on par with the skills of their more famous contemporaries in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley, Lamberg-Karlovsky says. Their creations display a rich repertoire of geometric designs, mythic monsters, and other creatures. Among them are striking humanoid statues with small heads and wide skirts, as well as horses, lions, snakes, and scorpions.

Wares in this distinctive style had long been found in regions as distant as Mesopotamia to the west, the shores of the Persian Gulf to the south, the Russian steppes to the north, and the great cities of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, which once flourished to the east—on the banks of the Indus River of today's Pakistan. Archaeologists had puzzled over their origin. Sarianidi's excavations seem to solve the puzzle: These items originated in the region around Gonur.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, a handful of Western researchers got word of Sarianidi's finds and began to investigate for themselves. Fredrik Hiebert, a young American graduate student, learned Russian, visited Gonur in 1988, and then a few years later returned with his Harvard adviser, Lamberg-Karlovksy. A team of Italians followed to dig at nearby sites and to examine Gonur's extensive cemetery. The Westerners brought an array of modern archaeological techniques, from radiocarbon dating to archaeobotany. U.S. labs determined that the early phase of the Gonur settlement dated to 2000 B.C.—five centuries earlier than Sarianidi had initially postulated—and that the people grew a wide variety of crops, including wheat, barley, lentils, grapes, and fleshy fruits.

The archaeological record shows that the site was inhabited for only a few centuries. The people of Gonur may simply have followed the shifting course of the Murgab River to found new towns located to the south and west. Their descendants may have built the fabled city of Merv to the south, for millennia a key stop along the Silk Road. Warfare among the Oxus people could have undermined the fragile system of oasis farming, or nomads from the steppes may have attacked the rich settlements. Sarianidi has found evidence that extensive fires destroyed some of Gonur's central buildings and that they were never rebuilt. Whatever the cause, within a short period Oxus settlements declined in number and size, and the Oxus pottery and jewelry styles vanished from the archaeological record. The large and square mud-brick architecture of the Gonur people may live on, however, in the clan compounds of Afghanistan and in the old caravansaries—rest stops for caravans—that dot the landscape from Syria to China.

Why the Oxus culture vanished may never be known. But researchers think they have pinned down the origin of these mysterious people. The answers are turning up in traces of mound settlements bordering the rugged Kopet-Dag mountains to the south, which rise up to form the vast Iranian plateau. The most prominent settlement there lies a grueling 225-mile drive from Gonur. At this site, called Anau, three ancient mounds poke up from the plains. Volunteer Lisa Pumpelli is working there in a trench at the top of a large mound with a spectacular view of the Kopet-Dag mountains. She is helping Hiebert, who is now an archaeologist with the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., track down the precursors to the Oxus culture. Both are following in the footsteps of Lisa Pumpelli's grandfather, Raphael Pumpelly, and great-grandfather, also named Raphael Pumpelly (Pumpelly is an alternate spelling of the family name). "I'm digging in my great-grandfather's back dirt," Pumpelli quips.

Trained in geology, the elder Pumpelly believed that Central Asia in ancient times was wetter and more fertile that it is now. He hypothesized a century ago that "the fundamentals of European civilization—organized village life, agriculture, domestication of animals, weaving, etc.—were originated on the oases of Central Asia long before the time of Babylon." Such assertions sounded radical—even outlandish—at that time, but Raphael Pumpelly was persuasive. An adventurer and son of an upstate New York surveyor, he convinced industrialist Andrew Carnegie to fund his expedition, charmed the authorities in Saint Petersburg into granting permission for a dig in 1903, and was even provided with a private railcar. He was 65 years old when he arrived.

The mounds at Anau, just off the Trans-Caspian railway, immediately caught Raphael Pumpelly's eye. A Russian general searching for treasure had already cut through the oldest of them, so Pumpelly and his son began there, using methods that were surprisingly modern in an era when most archaeologists were fixated on finding spectacular artifacts. "A close watch was kept to save every object, large and small . . . and to note its relation to its surroundings," Pumpelly wrote in his memoirs. "I insisted that every shovelful contained a story if it could be interpreted."

The close scrutiny paid off. One shovelful yielded material later determined to be ancient wheat, prompting Pumpelly to declare that Central Asian oases were the original source of domesticated grain. Although that claim later proved false—subsequent Near Eastern finds of wheat date back even earlier—it was the first recorded instance of serious paleobotany.

In 1904 a plague of locusts "filled the trenches faster than they could be shoveled," Pumpelly wrote, and plunged the area into famine, forcing him to abandon the dig. Traveling east, he noted the mounds dotting the foothills of the Kopet-Dag, indicating the sites of ancient towns similar to Anau that had survived on the water flowing down the slopes. Venturing northeast into the forbidding Kara-Kum desert, he examined locales along the ancient course of the Murgab River but turned back amid heat so brutal, he wrote, that "I gasped for breath." He had come just a few miles short of where Sarianidi would later find Gonur.

Pumpelly clung to his vision of an early civilization that thrived along the rivers flowing down from the Kopet-Dag. Years later, Soviet archaeologists working along the mountain foothills confirmed that as early as 6500 B.C., small bands of people were living in the Kopet-Dag, raising wheat and barley and grazing their sheep and goats on the mountains' foothills and slopes. That's a few thousand years after these grains were domesticated in the Near East but much earlier than most researchers had thought likely, supporting Pumpelly's view that Central Asian culture developed much sooner than commonly believed.

By 3000 B.C., the people of the Kopet-Dag had organized into walled towns. They used carts drawn by domesticated animals, and their pottery resembles the kind later found in Gonur. Many Soviet and Western archaeologists suspect that the Oxus civilization—at least in Margiana, the region in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan—evolved from this Kopet-Dag culture.

What prompted the settlers to abandon the Kopet-Dag and migrate into the area around Gonur? One possibility is drought, says Yale University archaeologist Harvey Weiss. He theorizes that the same drought that he claims destroyed the world's first empire—the Akkadians in Mesopotamia—around 2100 B.C. also drove the Kopet-Dag peoples from their homes. If the small streams that poured out of the mountains stopped flowing, life in the arid climate would have been impossible. That would have forced the people of Kopet-Dag to head toward Gonur and settle by the Murgab River, the only reliable source of water in the Kara-Kum. With its headwaters in distant Hindu Kush glaciers, the river would have continued flowing even in the hottest summers or longest droughts.

Another possibility is that population growth forced people down from the mountain slopes and onto the plains, where the Murgab then flowed lazily into a delta, creating an oasis of dense brush teeming with game, fish, and birds. That could explain why so many Oxus sites are built on virgin soil, as if carefully planned in advance. "The people came from the foothills of the Kopet-Dag with baggage, a knowledge of agriculture, irrigation systems, metal, ceramics, and jewelry making," says Iminjan Masimov, a retired Russian archaeologist who once excavated Oxus sites in Margiana.

Indeed, many Kopet-Dag sites appear to have been abandoned about 2000 B.C., just around the time Gonur and nearby sites took root. Hiebert's excavation at Anau, however, shows that it at least remained inhabited even as Gonur flourished.

While scholars debate the relationship between the Oxus culture and other early urban settlements, there is no dispute about the importance of the Kopet-Dag as a natural highway for nomads, traders, and armies between the Central Asian steppes and the Iranian highlands. The evidence is unmistakable when Hiebert shows me around the ruins of a medieval mosque on the summit of one of Anau's mounds. Damaged by time and earthquakes, the edifice is still famous for the two serpent-dragon mosaics—showing more the influence of China than of Mecca—that once guarded its facade. Around us are hundreds of mysterious little constructions, Stonehenge-like, each made of three small bricks. Hairpins and bits of cloth—probably linked to Central Asian shamanism—are scattered about the hilltop. Women come here to pray for children. One family, three generations of women, sits silently in a row by a tomb. Hiebert casually picks up glazed Iranian ware and a bit of Chinese blue pottery. "Here is your Silk Road," he says.

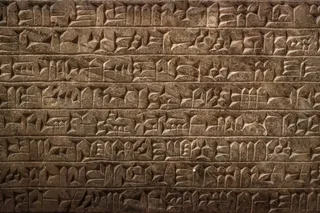

The find dovetails with Sarianidi's work at Gonur, where he has found a Mesopotamian cuneiform seal not far from an Indus Valley stamp bearing symbols above an etched elephant. Both lay near small stone boxes similar to those manufactured in southeastern Iran. These items provide tantalizing hints of commercial traffic on a Silk Road predating by two millennia the trading route that eventually linked China to Europe in the early centuries A.D. Hiebert likens the Oxus civilization to Polynesia—a scattered but common culture held together by camels rather than canoes.

Sarianidi sees the settlers of the Oxus region as traders, not just in goods but also in faith. For him, Gonur is the capital of a people who came from the West with a religion that evolved into Zoroastrianism. In the long, still desert evenings at his camp, he speaks of migrants fleeing from drought-plagued Mesopotamia to this virgin land, bringing a conviction that fire is holy, as well as techniques for brewing a hallucinogenic drink called soma. Eventually, some wandered farther east, part of the migration of Aryans on horseback who conquered India about 3,500 years ago. This theory of his finds little support, however. "Sarianidi has persuaded few if any archaeologists of his strongly held opinions," says Lamberg-Karlovsky.

Sarianidi may be the last archaeologist in the mold of the 19th-century adventurer, with a larger-than-life swagger, a sharp tongue, and a thick stubborn streak. Few researchers today can claim to have laid bare acres of ancient settlements virtually unknown a generation ago. The desert freed Sarianidi from the repression of the Soviet Union. In return, he uncovered the lost history of the desert.

On the excavation team's last night at Gonur for the season, we picnic in the desert, reclining on rugs and pillows like Turkomans, toasting with vodka like Russians, and enjoying roast lamb as Oxus shepherds no doubt did four millennia ago. "Here you understand who you are," Sarianidi says, lying like a pasha on his cushions. A stocky and robust man, he looks worn, almost frail, in the twilight. "I am one of those who cannot go on living without the desert. There is no place like this in the world. I want to be buried here."