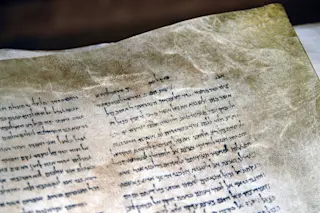

The Dead Sea Scrolls are more than just ancient manuscripts discovered in the Qumran Caves; they represent a unique narrative that extends beyond their discovery in the mid-20th century. Their journey is not just a physical one, but also an intellectual and cultural voyage marked by scholarly research and debates over ownership.

Uncover the layers of history, knowledge, and controversy the Dead Sea Scrolls have accumulated over the decades.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a collection of ancient Jewish religious manuscripts. These scrolls hold significant religious, historical, and linguistic importance.

Qumran Cave where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found in Israel (Credit: Sopotnicki/Shutterstock)

Sopotnicki/Shutterstock

In 1947, teenage Bedouin shepherds found jars in a cave on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea. Seven scrolls were inside the jars, including the Isaiah scroll, which was 24 feet long. Written in Hebrew, it told the entire Book of Isaiah, and it was ...