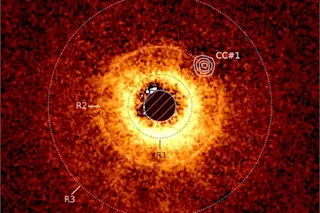

It's the 1840s. Rival astronomers in Britain and France separately toil away in their notebooks, fiercely guarding their calculations of just where a planet beyond Uranus might be hiding, hoping that they and their country will get the glory for finding it. When telescopes finally spot Neptune, the discovery leads to decades of debate over primacy, and scouring each man's private data to determine who deserved the most credit. Fast forward to the 21st century: Rivalries may have changed, but in the hunt for new planets—especially becoming the first to detect a new world like our own in a distant star system—defending one's data to lay claim to discovery has not gone away. This week the team behind NASA's planet-hunting space telescope, Kepler, announced that it has found more than 700 new candidates for exoplanets. Given that the current tally of known planets beyond our solar system stands near 460, ...

Astronomers Find a Bevy of Exoplanets; Won’t Discuss Most Interesting Ones

NASA's Kepler telescope reveals over 700 new candidates for exoplanets, sparking excitement for Earthlike planet discovery.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe