For a team of researchers studying the effects of stress on ancient humans, their work wasn’t exactly like pulling teeth — but it did involve examining their enamel.

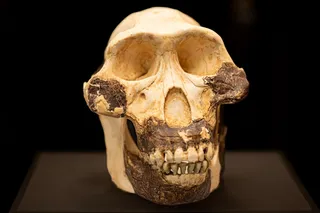

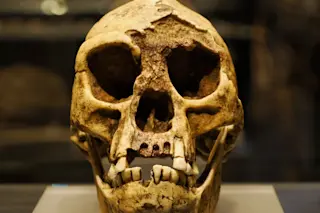

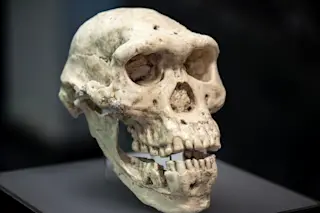

A study in Scientific Reports that used enamel defects as a proxy for stress, says that Neanderthal children (who lived between 400,000 years and 40,000 years ago) and Upper Paleolithic kids (who lived between 50,000 years and 12,000 years ago) experienced similar levels of stress — but at different times during their development.

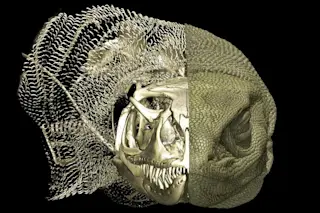

So, why enamel? Because dental enamel forms during childhood and does not remodel, it preserves a record of childhood growth. As the enamel is laid periodically, regular growth patterns can usually be observed on the enamel surface, explains Laura Limmer, a professor at the University of University of Tübingen in Germany and an author of the study.

“Physiological stress, such as malnutrition, infections, etc., has been found to cause ...