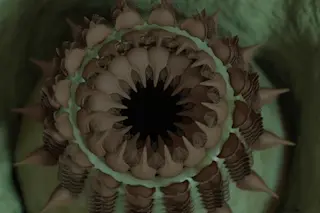

A University of South Florida geoscientist says the key to finding missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 could rest with analyzing barnacles. Attached to its debris, some barnacles have already been recovered from locations around the Indian Ocean.

His work so far with barnacles recovered from a flaperon (a type of aileron) has produced a partial map showing how the debris likely moved across the ocean. A future map leading to the crash site could help to renew the official search effort, which ended in 2017.

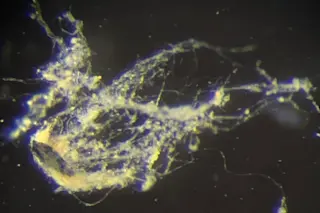

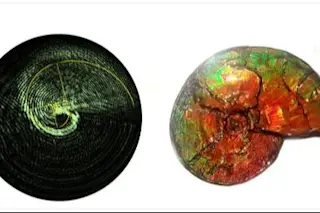

The method developed by associate professor Gregory Herbert reveals which water temperatures a barnacle has passed through based on the chemical makeup of its shell. As barnacles grow a small amount each day, the chemical changes record a detailed history of where the barnacle has been.

In a recent study, Herbert carried out a growth experiment with live barnacles to record the chemistry for each ...