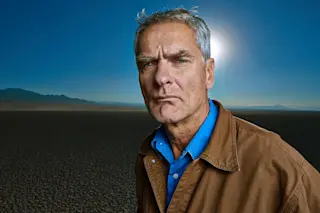

Chris McKay likes to travel, preferably to exotic, faraway lands. Mars is the usual destination, but Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moons Enceladus and Titan are also on his itinerary.

McKay, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, ventures to some of Earth’s most extreme environments to study the closest facsimiles he can find to Mars and other distant outposts, on a mission to learn how life might exist beyond our planet.

Over the past 30 years, McKay’s adventures have included an invigorating swim in an Antarctic lake beneath more than 10 feet of ice. He’s endured black clouds of mosquitoes in the Siberian permafrost zone and prepared for polar bear attacks in the northernmost reaches of the Canadian Arctic. He’s squirmed through tunnels no wider than a watermelon in the bowels of America’s deepest cave, more than 1,000 feet below Earth’s surface. While the work can be exhilarating ...