It’s an increasingly common story in football: When experts examine the brains of former players, they find that many have a disorder called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a type of brain degeneration caused by years of repeated head injuries and concussions. The result is an often tragic situation that can cause aggressive behavior, a loss of memory and cognitive function, and in some cases, violence, depression and suicide.

Aaron Hernandez was only 27 when he died. The former New England Patriot was convicted of murdering a man in a fit of rage before committing suicide in his jail cell in 2017. Experts posthumously diagnosed him with CTE, along with a number of players that have fallen on similarly tragic circumstances. The numbers, meanwhile, are staggering. One study found when the brains of deceased former football players were examined, 87 percent of college players and 99 percent of NFL players had CTE, a condition that was once considered rare.

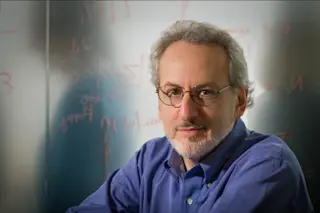

That’s why researchers are in a rush to protect players from the condition. Most recently, players at the University of North Carolina were equipped with “smart mouth guards” with built in sensors that record player data including the speed, direction, force, location and severity of play hits. Jason Mihalik, who heads up the school’s concussion research program, says that the data gathered from the mouth guards could be used to make important changes to football rules.

For starters, they might be able to help researchers see where the most dangerous hits are happening — and what can be done to reduce them.

The Danger at Kickoff

Mihalik and his team previously used helmets with built-in sensors to collect epidemiological data that helped motivate important changes to kickoff rules. But recently, these newer mouth guards were found to even more accurately read how hits and tackles impact the brain. Kickoffs have been increasingly under fire because players run directly at each other and can build up speed before impact. A 2018 study showed that while kickoffs represent just 6 percent of plays, they represent 21 percent of all concussions in college football. In 2018, the rule was changed so that kickoff receivers can make a fair catch inside the 20-yard line, and players on the kicking team will not be allowed to receive a running start. This way, players aren’t charging at each other full speed as often.

But while Mihalik says that mouth guards can tell us a lot, they can’t yet tell us when to pull someone from the game. While researchers can design a mouth guard that can detect just about anything, analyzing and interpreting that data is another story. “We’re not sure why a certain player can get hit with a certain impact in a certain direction and get a concussion while another player can be hit exactly the same way and not get a concussion,” says Mihalik.

According to Gregory W. Stewart, co-director of the Sports Concussion Management Program at the Tulane School of Medicine, smart mouth guards are simply another tool in trying to help us understand what happens with impact brain injury. But there’s still a lot we don’t know about the other conditions that increase a player’s vulnerability to head injuries.

Still, Stewart says the mouth guards can help give us a broader look at the game. "They can help us look at run plays, passing plays and certain positions that we need to pay special attention to in terms of head injuries.”

Position-Specific Helmets

Stewart says that the mouth guards may also help build data around another tool for injury prevention. Researchers like himself are looking into position-specific helmets that could be produced with additional padding in areas where the player is most likely to sustain hits.

Some issues are harder to address than others. Special teams plays and kickoffs remain dangerous even after rule changes, meaning that finding alternatives to kickoffs and punts could go a long way in preventing injury. Players are also vulnerable to concussion when they sustain two hits close to one another. For example, when a player takes a hard hit and then hits his head on the ground within a few seconds. This, says Stewart, is harder to prevent with rule changes because getting tackled and going to the ground is embedded in the nature of the game itself.

It’s not clear how big of an impact these smart mouth guards will make on the future of football. So far, the Tar Heels are wearing them, as are players at the University of Alabama, University of Wisconsin and the University of Washington. A number of NFL teams have been using them, too.

But currently, head injuries are still a constant specter plaguing the game. In all, 55 percent of concussions in college sports occur in football. That doesn't change the fact that college and NFL football are among the most popular sports in the U.S., even if that popularity has faded slightly in recent years. (In 2017, 57 percent of Americans identified as fans of professional football, compared to 67 percent in 2012.) That’s why, says Stewart, “it’s about modifying the game to protect the athletes without fundamentally changing the sport.”