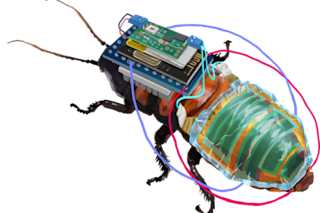

Credit: Disney | Marvel Entertainment When Paul Rudd's character puts on his superhero suit in the Marvel film "Ant-Man," he gains the ability to shrink to the size of an insect to infiltrate the tightest security systems. Despite his tiny stature, he can punch and throw around full-sized foes with human strength. He even commands ant swarms to do his bidding. The "Ant-Man" suit technology may represent a comic book fantasy, but many real-life military forces have attempted to harness the power of insects throughout human history. Military commanders have historically used insects to directly attack enemy soldiers, destroy crops and other food supplies, and as carriers of deadly infectious diseases, according to Jeff Lockwood, professor of natural sciences & humanities at the University of Wyoming. In his book “Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War,” Lockwood points out many such uses of insects in both ancient and modern ...

'Ant-Man' Dreams of Harnessing Six-Legged Soldiers

Explore how Ant-Man superhero strength reflects real-life strength of ants and the potential for insects in warfare.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe