Sauropod dinosaurs — from classics like Apatosaurus to the recently-named Patagotitan — were giants of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, the largest species attaining lengths exceeding 100 feet and weighing more than 80 tons. And while there are multiple reasons why these reptiles grew to such imposing sizes, paleontologists are still uncovering the biological particulars that allowed these exceptional dinosaurs to exist. Among them, researchers have learned, were cushioned feet.

Paleontologists have been pondering sauropod feet for a long time. Footprints and trackways left by these dinosaurs show how the bottoms of their feet had soft pads on the underside of the toes. Modern elephants have a similar anatomical setup. But it wasn’t until now that experts understood just how important these pedal pillows were to the evolution of truly gargantuan dinosaurs; stress tests of virtual dinosaur bones, detailed earlier this year in Science Advances, highlight how soft tissues helped support the sturdy bones of the sauropods.

Read More: Why Were Prehistoric Marine Reptiles So Huge?

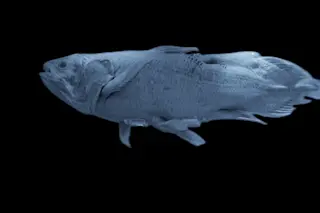

Although experts have extensively studied various parts of sauropod skeletons, paleontologist Andréas Jannel of the Natural History Museum in Berlin and his colleagues write that fossils of complete sauropod feet are relatively rare. Using 3D models of feet from dinosaurs such as Diplodocus, Camarasaurus and Giraffatitan, the researchers used an engineering technique called finite element analysis to study how the presence or absence of a foot pad — as well as different foot positions — affected the mechanical stresses and strains a standing sauropod coped with.

Break a Leg?

Understanding how an animal holds their feet is a complicated task. Some animals, such as bears and humans, are plantigrade. This means the entire foot, from toes to heel, touches the ground. But many other animals, like cats and birds, are digitigrade. They’re effectively standing on tip-toes, like you might do when trying to reach the cookie jar on top of the fridge.

For a long time, paleontologists thought sauropods were flat-footed, plantigrade animals. But Jannel notes that the dinosaurs have an arrangement that is a little strange: The earliest sauropod ancestors were digitigrade. Instead of switching foot postures, however, the pads at the bottom of their feet formed cushions that allowed more contact with the ground. “Sauropods retain a digitigrade foot skeleton but the soft tissue pad makes their foot functionally plantigrade,” Jannel says.

The paleontologists devised new tests to determine whether these foot pads were truly necessary or simply anatomical extras, like the human tailbone. A key consideration of the tests were what experts know as “von Mises stress.” It’s a formula that engineers and other researchers use to determine if a material under study will withstand mechanical stress — like the forces involved when a big dino stands on an ancient plain — or instead break.

In every case, Jannel and his coauthors found, adding soft tissue pads to the models reduced the amount of stress the sauropod foot bones were under — regardless of whether the bones were closer to being flat on the ground or up on the tips of their toes. On the flip side, tests without the soft tissue pads were much more prone to fracture. The dinosaurs were so massive, in fact, that they would have broken their own bones with a single step if they didn’t have a pillow of soft tissue underneath.

“What was astonishing to me was that the model’s results clearly show that the foot bones of sauropods break under any realistically conceivable foot posture without the foot pad,” says Stockton University paleontologist Matthew Bonnan, who was not involved in the new study. Even though paleontologists have yet to find a fossilized sauropod foot pad (a tall order, given that they likely decay away quickly and even complete sets of sauropod foot bones are hard to find) the biggest dinosaurs must have had them.

Titan Trailblazers

The fact that this feature was so essential to sauropod size led Jannel’s team to reconsider when the pads evolved in sauropod history. These giants belonged to a broader group called sauropodomorphs that go back to the earliest days of the dinosaurs; back then, the ancestors of Apatosaurus and Diplodocus were small, lightly built animals that ran around on two legs. Fossil tracks, however, show that sauropods had expanded heel pads very early in their history.

The feature would only be elaborated through time as the creatures grew larger. By about 200 million years ago, a lineage of the bipedal sauropodormophs had split off to move around on four legs. Surely these first sauropods could evolve to be so big because they’d inherited the soft tissue pads from their ancestors.

The new study even helps paleontologists understand the tiny details of how sauropods stepped, though we’re 66 million years too late to witness them walk around. The dinosaurs walked heel-to-toe like elephants, Bonnan says, but put more pressure on the inside surface of the foot, toward the midline on the body, and had very mobile toes. That flexibility likely helped redistribute weight as these dinosaurs moved, their anatomy building upon what sauropods inherited from their earliest predecessors.

The research resolves what paleontologists have only been able to speculate about for 120 years: The pads were part of a constellation of different features that opened evolutionary opportunities for sauropod dinosaurs to become exceptionally enormous. Egg-laying, forgoing chewing, and lightweight bones filled with air sacs also had their roles to play, allowing Diplodocus and family to surpass what’s been possible for any land-dwelling mammal since.