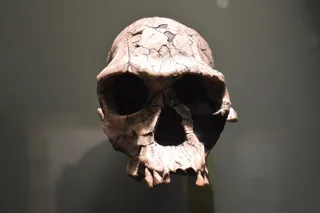

When Homo neanderthalensis first came in contact with Homo sapiens around 50,000 years ago, in what’s now the Middle East, they encountered a host of diseases for which humans had no immunity for because they had never experienced them before.

But, interbreeding would change the human genome, which likely continued until Neanderthals went extinct around 40,000 years ago. And even today humans are left with some Neanderthal genes, many of which pertain to the immune system.

Interbreeding and Human Immunity

Interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals allowed for genetic segments in the genome — many of which were deleterious to humans, but some of which were helpful — to spread amongst the population, says Dmitri Petrov, an evolutionary biologist at Stanford University.

“The segments that were adaptive and spread tended to be proteins that interacted specifically with RNA viruses,” he says.

Other research has shown that these viruses had an impact on the modern immune system. They likely gave humans an immunity boost and provided resistance to diseases that they had not come in contact with previously. RNA viruses can include things like Hepatitis A, dengue, Zika, yellow fever, and West Nile virus, amongst many others, although Petrov and his team did not identify particular types of RNA viruses in their research.

This new immunity might also have had a downside in the form of allergies that come with a hypersensitive immune system. The inheritance of some genetic segments as a result of interbreeding left many humans with seasonal allergies, an overreaction to a perceived challenge to the immune system.

Read More: DNA Analysis Reveals 7,000 Years of Human-Neanderthal Relations

Did Neanderthal Viruses Lead to Their Extinction?

Persistent infections, meaning diseases that don’t immediately kill you but instead slowly chip away at your body, have been thought by some experts to be one of the potential causes of the extinction of Neanderthals, according to a study published in the May 2024 edition of Viruses.

These diseases, which included adenovirus, herpesvirus, and papillomavirus, were preserved in the bones of Neanderthals. Life-long infections like these would have made it hard for archaic humans living in already difficult conditions to do things like hunt, gather, reproduce, or just get by, thereby shortening their lifespans.

“If you have ebola, you die in a day or so, but these viruses have a different type of strategy,” says study author Marcelo R. S. Briones, a geneticist and professor at the Medical School of the Federal University of São Paulo. “Although their mortality is not that high, their morbidity (health problems that they cause) is high.”

His research has shown that we can go back to the time of Neanderthals and still detect the viruses that were present. Briones downloaded the entire Neanderthal genome from samples found in the Chagyrskaya cave in Russia.

“These samples were collected with great care to avoid contamination with modern DNA as opposed to earlier Neanderthal genomes,” says Briones.

Read More: Neanderthal vs Homo Sapiens: How Are Neanderthals Different From Humans?

Leaving Their Mark

Earlier samples were collected and sequenced from museum specimens where people had handled the bones, which causes contamination. While persistent infections are still hypothetical as a cause of Neanderthal extinction, Briones did uncover them in the genome, so we know they were present.

Neanderthal viruses had an impact on these early humans before they went extinct. They likely affected their ability to survive and compete with other early humans and may have eventually caused or at least contributed to their extinction.

And they also left their mark on humans, who would adopt the diseases that they had never been exposed to before leaving Africa and eventually garner at least some immunity. Today, 40,000 years later, long after the Neanderthal extinction, we still have them locked away in our genomes.

Article Sources:

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

The Journal of Biological Research. Hominin interbreeding and the evolution of human variation

Dmitri Petrov, an evolutionary biologist at Stanford University

Institut Pasteur. Neanderthal genes gave modern humans an immunity boost, allergies

Cell. Evidence that RNA Viruses Drove Adaptive Introgression between Neanderthals and Modern Humans

Viruses. Reconstructing Prehistoric Viral Genomes from Neanderthal Sequencing Data

Marcelo R. S. Briones, a geneticist and professor at the Medical School of Federal University of São Paulo