This story was originally published in our January/February 2022 issue. Click here to subscribe to read more stories like this one.

The development of the mRNA vaccine — a breakthrough in its field, instructing cells to produce their own protection without the risk of giving someone the virus — was fast and furious, made possible through rapid genome sequencing.

But its origins go back to the late 1980s, when Kati Kariko, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, began experimenting with placing mRNA (m stands for messenger) into cells to instruct them to produce new proteins, even if those cells had been previously unable to do so. Eventually, Kariko also discovered that pseudouridine, a molecule of human tRNA (t stands for transfer), could help a vaccine evade an immune response when added to the mRNA –– laying the groundwork for a first-of-its-kind antidote that helped save hundreds of thousands of lives in 2021, becoming the vaccine of choice for our times.

The implications of this breakthrough in 2005 were huge: Cells, it turned out, could be harnessed into producing protein without triggering an immune attack. Furthermore, synthetic mRNA could be used instead of putting an actual virus into the body to produce a vaccine.

Research continued. By the end of 2019, American biotechnology company Moderna and Germany’s BioNTech (a partner with Pfizer), had been researching mRNA flu vaccines for several years. This work put them in a position to respond quickly when COVID-19 emerged. Within mere hours of Chinese scientists posting the coronavirus’ genetic sequence in January 2020, BioNTech had developed its mRNA vaccine. Days later, Moderna had its own. Other hurdles to implementation, such as clinical trials, approvals, mass production and distribution, would take several more months — unprecedented rapidity in the world of vaccine development, yet not fast enough for millions across the globe who were sick and dying from the virus.

By November 2020, clinical results found that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was a potent antidote to COVID-19, showing a 95 percent efficacy against the virus. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted emergency-use authorization and the first shipments of the vaccine were delivered in December 2020. To date, billions of doses of COVID vaccine have been injected into arms around the world.

Need for Speed

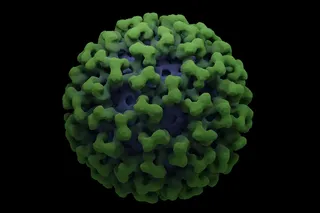

So how does it work? Once mRNA (encased in a lipid bubble) is injected, the vaccine attaches to a cell, instructing it to produce a harmless replica of the spike protein — the significant marker of the coronavirus, which allows COVID-19 to inject itself into human cells –– triggering an immune response. Because mRNA does not enter or interact with the cell nucleus, it does not alter human DNA. Once the cell uses the instructions, it breaks down the mRNA.

As opposed to the time it takes to produce traditional vaccines, created with inactivated viruses and therefore time-consuming and expensive, mRNA can be produced almost instantly.

It’s been a “game changer,” says Tom Kenyon, chief health officer at Project HOPE and former director of global health at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where he spent more than two decades combating global diseases. In comparison with other pandemics, such as HIV, “the science in COVID-19 has moved much faster,” Kenyon says, because “all that research and investment has paid off. These are vaccines that give very strong immunity, which we never had in previous attempts.” Now, he believes, we can develop effective vaccines much faster, which could ultimately help get ahead of future pandemics.

“It’s not just the speed, it’s the efficacy of the vaccine that’s so incredible,” Kenyon says. “That’s what gives everybody in the public health community hope.”

John Kokai-Kun, director of external scientific collaboration for biologics for USP, a nonprofit focused on building trust in the supply of medicines, says that mRNA will be “the technology of choice for most future vaccines.” Kokai-Kun, who spent most of his career working on the research and development of antibacterial drugs and vaccines, also sees the speed of production in the lab as the key benefit of mRNA.

“You can just type the sequence into a computer and just make a synthetic RNA molecule,” Kokai-Kun says. “You don’t have to make cell banks and seed banks and viral stocks and clone things. It’s almost a plug-and-play type of scenario.”

Cancer Challenger

The development of mRNA technology has implications far beyond COVID-19, and could be used to combat HIV, influenza and malaria. It also shows tremendous promise against new viruses with epidemic potential, such as avian influenza and other respiratory viruses. But its potential to treat cancer, which it can do by provoking the immune system to target cancer cells, is especially exciting. Most traditional immunotherapy for cancer uses “passive immunity,” where a drug acts as the antibody and doesn’t always last long. But active immunity, achieved with mRNA, means the body can remember how to create the response on its own.

The biggest drawback, currently, is production capacity. Many parts of the world would need help setting up the capability to produce these vaccines, and to scale more rapidly. “The mRNA story is by far the greatest story of this pandemic, and it’s an amazing scientific accomplishment, but we haven’t translated that yet into programmatic results, and that’s what matters,” Kenyon cautions.