It’s sometimes called the “Transylvania effect.” In the dark sky, the clouds shift, revealing the full moon’s eerie silver gleam, and the people on Earth below go mad. It’s a story that gets repeated by doctors, teachers and police officers. The science, though, says something different.

Blaming the full moon for strange behavior is a time-honored tradition. In the first century AD, the Roman philosopher Pliny suggested that the full moon caused more dew to form, which led to increased moisture in the brain, and that, he said, led to madness.

The idea that the full moon makes people crazy didn’t go out of fashion along with togas, though—in the 1700s, a British legal expert and judge wrote, “A lunatic, or non compos mentis, is properly one who hath lucid intervals, sometimes enjoying his senses and sometimes not and that frequently depending upon the changes of the moon.” (The word lunatic, by the way, comes from the Latin luna: moon.)

In the 1970s, a popular book posited that just as the moon controls the tides, its gravitational pull affects the fluid sloshing around in human brains. Even today, you might hear stories about classrooms of students misbehaving and people getting hurt in freak accidents around the full moon. But there’s one big problem with all these theories: they’re not true.

Full Moon Fever

For decades, researchers have pored over hospital records and police blotters, and time and time again, they’ve come up with the same answer — the full moon doesn’t seem to be associated with more strange things happening than usual. No uptick in births, no synced up menstrual periods and no madness.

“I’m not aware of a single replicated finding in the literature that there’s a link between the full moon and odd behavior,” says Scott Lilienfeld, a professor of psychology at Emory University. Often, studies that do make this claim don’t hold up to scrutiny. In one paper, researchers posited that there are more car crashes during the full moon. They later retracted it after realizing that many of those full moons were on weekends, when more people are on the road. But despite the lack of evidence, lots of people still believe that the full moon makes things… weird.

But despite the lack of evidence, lots of people still believe that the full moon makes things… weird.

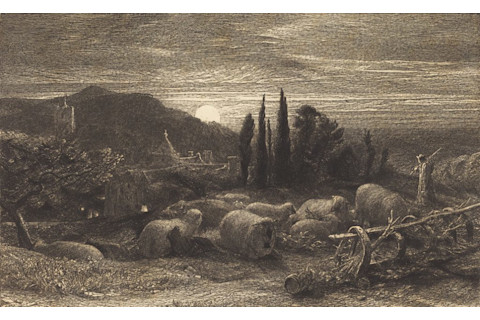

The Rising Moon, by British painter Samuel Palmer. (Credit: National Gallery of Art)

National Gallery of Art

Rationalizing Lunacy

It’s not quite clear where the superstition came from in the first place. But in defense of believers of “lunacy,” the moon does exercise some influence on Earth, from the pull of the tides to the mating cycles of corals and glowworms. It’s not surprising that people wondered if the moon might be shaping their lives too.

Lilienfeld notes there might be some correlation at work, if not necessarily causation. Before artificial lighting, the full moon might have kept people up at night, including people with mental illnesses that are exacerbated by lack of sleep. The bright sky could have led them to leaved their houses and congregate, says Lilienfeld, “And that may have caused a commotion.”

But no matter where the idea came from, it was probably easy for people to find evidence for their suspicion that bad things happened when the moon was full. “Our brains tend to be predisposed to seeing patterns, even when they’re not actually existent,” says Lilienfeld. “Once people have an idea in their head that the full moon is linked to odd behaviors, […] they may end up seeking out, even unintentionally, instances in which there is a full moon and something strange happens.” We don’t pay attention to the uneventful full moons, but the strange ones stand out.

This pattern of thinking, where we pay extra attention to things that might be dangerous or important, is an example of what psychologists call cognitive bias. It might be hardwired into the way we think, as a means of self-preservation. If you’re walking in the forest and a snake-shaped something springs out at you, you’ll jump out of the way in case it’s a snake. But more often than not, you just stepped on a stick. It makes evolutionary sense to move, though, just in case — our brains operate on a “better safe than sorry” model. The same goes for keeping an eye on the full moon.

And while cognitive bias could protect us from a branch/snake, superstitions like assigning power to the full moon might protect us in a different way.

“The world is very scary, and the world is unpredictable, and it may give us a pleasure, a relief, to think the world is not as uncontrollable, not as unpredictable as we might believe,” Lilienfeld says. “Whether it applies to the full moon, I don’t know, although I do suspect that anything that gives us a sense that we can predict something might provide us with a measure of psychological reassurance.” Things break, people break, and it’s nicer to think that it’s the fault of a bad moon rising than that the world is just a strange place no matter what the sky looks like.