We think big. We think out loud. We think outside the box. We think on our feet. But what we don’t do is think entirely inside our heads. Thoughts aren’t confined to our brains — they course through a network that expands to our bodies, perhaps eliminating, at times, the need for complex thought.

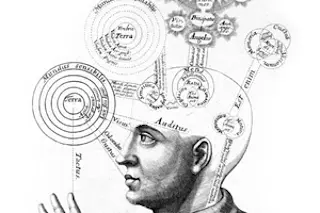

The notion that we think with the body — the startling conclusion of a field called embodied cognition — flies in the face of long-standing views. Early cognitive psychologists defined thought as an activity that resides in the brain: Sensory data come in from eyes and ears, fingers and funny bone, and the mind turns these signals into disembodied representations that it manipulates in what we call thinking.

Sure, the body may collect sensory information, like a computer collects information via mouse and keyboard, but according to the traditional view of cognition, it’s the brain that does the thinking.

But dozens of studies over the past decade challenge that view, suggesting instead that our thoughts are inextricably linked to physical experience. As University of Toronto psychologist Spike Lee puts it, bodily states “aren’t some extraneous thing — they’re part of the thinking process.”

In one study, Lee and a colleague exposed volunteers to different odors. When they did, they found that getting a whiff of a fishy odor evoked feelings of suspicion; likewise, when research participants were exposed to another person behaving suspiciously, they were better able to detect a fishy scent.

The range of findings demonstrating embodied cognition is impressive. A small sampling: Looking upward nudges people to call to mind others who are more powerful, while looking down prompts thoughts of people we outrank.

People judge a petition to be more consequential if it is handed to them on a heavy clipboard rather than a lightweight one. Baseball players with high batting averages perceive the ball as bigger than poorer hitters. And Botox injections that prevent frowning also slow people’s comprehension of sentences describing angry and sad events.

Thinking Is for Doing

On their surface, findings like these seem like mere fodder for amusing cocktail conversation: “The body biases thought, you say? Hmm, weird. Pass the guacamole.” But some cognitive scientists argue the evidence points to something far deeper and more radical. It’s not just that our bodies influence thought: It’s that thought itself is a system that simultaneously takes place in the brain, the body and the environment around us.

In fact, we fundamentally perceive the world in terms of our ability to act on our environment, says Sabrina Golonka, a cognitive psychologist at Leeds Metropolitan University in the United Kingdom. “We’re not seeing the world in inches and feet — we’re seeing the world in arm units or leg lengths,” she says.

In one study, researchers at the University of Virginia asked volunteers to estimate the steepness of a hill just by looking at it from the bottom. The volunteers’ answers correlated with how physically suited they were to climbing the hill: They rated the hill as steeper when they wore a heavy backpack, and likewise, athletes described the hill as less steep than volunteers who were unfit.

The body’s influence over our perceptions is more than just academic — it could have serious consequences in high-stakes situations, argues Jessica Witt, a psychologist at Colorado State University. She wondered if embodiment could help explain tragic misperceptions such as the 1999 shooting of Amadou Diallo, who was killed by New York police officers who perceived Diallo’s motioning to open his wallet as the brandishing of a gun.

Thinkstock

To investigate, Witt and a colleague showed college students photos of people holding different objects and asked them to quickly decide whether what they saw was a gun or some neutral object, like a shoe or a cell phone.

When participants were themselves holding a plastic toy gun, versus some neutral object, they were about 30 percent more likely to perceive the object in another person’s hand as a gun. Merely seeing a gun nearby had no such effect on their perceptions.

“We see the world in terms of our ability to act,” Witt concludes. The same object “can look different, depending on what we’re intending to do and our ability to perform that intended action.”

Different Bodies, Different Thoughts?

Such findings raise a mind-bending question: Do different bodies dictate different thoughts? In one study that confronts that idea, cognitive scientist Daniel Casasanto of the New School for Social Research in New York reasoned that if people use their physical perceptions and motor experiences to construct mental simulations, then physical characteristics that cause us to interact with the environment in systematically different ways should in fact send people down different mental pathways.

To test the possibility, Casasanto and colleagues examined spatial preferences in left- and right-handers. He found that people prefer the choices presented to them on their dominant side, a phenomenon that supports what he calls the “body-specificity hypothesis.” When asked to select which job applicant to hire, which product to buy or which alien creature seemed most trustworthy, lefties tended to choose the selection that was on the left, and vice versa.

In another experiment, Casasanto’s team asked right-handed study participants to wear a bulky glove that nudged them to use their left hand while doing a motor task. The constraint changed their preferences: After completing a motor task with their left hand, people preferred choices presented on their left.

Studies that demonstrate embodied cognition seem to defy conventional wisdom, which paints thought as a set of computer-like algorithms that unfold entirely within the skull. That characterization is a mistake, Golonka argues.

She and Leeds colleague Andrew Wilson advocate an ecosystem-like approach that treats even the most sophisticated cognitive tasks as a product of how our brains and bodies have evolved with our environments. The astonishing implication is that our bodies, through perception and action, can actually replace the need for complex mental calculations.

Consider a baseball outfielder who must run to catch a fly ball: How does he get to the right place at the right moment? You could solve this problem with a calculator, using math and physics to calculate where and when the ball would reach the height necessary for catching, and then draw a straight line from the player’s starting position to that spot. But the player doesn’t do the math, and he doesn’t run in a straight line, Golonka says.

Instead, he keeps his eye on the ball and moves in a path that syncs with the ball’s curved, decelerating trajectory. As he runs, his motion cancels out some of the ball’s motion and now it looks, to him, as if the ball is moving in a straight line, which he can track to its endpoint.

The outfielder doesn’t need to get out a calculator. He just needs to process the visual cues he’s getting, along with physical cues like his running speed, and then put them together to solve the task. Yes, he uses his brain; but his eyes and legs are just as crucial.

Clear evidence of embodied cognition is now voluminous. What to make of it ... well, that’s more controversial. The view that thought depends crucially on bodily sensation and action has yet to overtake the traditional model of cognition, as Lee observes. In part, that’s because researchers lack a coherent theory that can explain how and under what circumstances embodied effects occur.

Golonka and Wilson hope their ecosystem-like model can become this unifying framework. If they’re right that thought occurs not only in the brain but in a tangled communication among brain, body and environment, it could turn cognition research upside down. French philosopher René Descartes once said, cogito ergo sum: I think, therefore I am.

The embodied cognition model suggests a slightly different philosophy — I am, therefore I think.