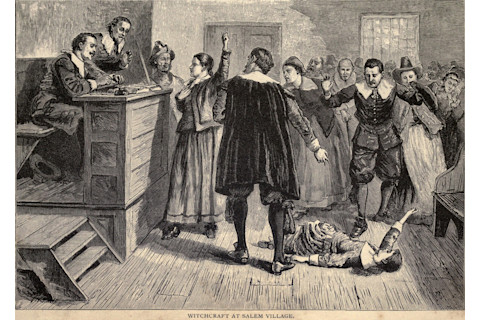

The terror began in December 1691 in Salem, Massachusetts. Girls in the village began acting strangely. They spoke with slurred speech and had seizure-like fits. Sometimes they were quiet and melancholy. Other times, they were manic.

The first to exhibit odd behavior was Abigail Williams, the 8-year-old niece of the reverend. Her family considered her well-behaved and they were frightened when she cried that someone — who they couldn’t see — was pinching and biting her. Area doctors examined the girls but couldn’t explain their sudden hysteria.

What Really Happened During the Salem Witch Trials?

(Credit: Everett Collection/Shutterstock)

Everett Collection/Shutterstock

In February 1692, one of the doctors blamed witchcraft for their afflictions. Frenzied authorities pressed the girls to name the witches who tormented them. Over the next eight months, dozens of villagers were arrested and tried for witchcraft. Twenty people were executed for the crime, as well as two dogs.

These legendary trials have had many explanations: Some historians dismissed the accusers as teenage girls who just wanted attention. Others argued the accusations were part of a financially-driven plot to take over land and resources.

But what if the victims were actually under the influence of tainted grain?

Read More: How Superstitious Europeans Scared Away Witches

Poisoning May Explain Witchcraft Accusations

Rye with ergit fungus growing on it (Credit: PHOTO FUN/Shutterstock)

PHOTO FUN/Shutterstock

Behavioral psychologist Linnda Caporael first suggested the possibility in 1976 when she was a doctoral student in psychology. She argued the summer of 1691 had been wet and hospitable for ergot, a type of fungus that grows on grain — typically rye — in wet conditions. The fungus, Claviceps purpurea, resembles grain when it grows on the crop. Until the 1800s, farmers assumed it was part of the plant and they put it through the mill without realizing it was a toxic fungus.

But ergot is also a hallucinogenic; LSD, most notoriously, is derived from it. Once ingested, there are two responses to ergot poisoning, or ergotism: Convulsive ergotism causes fits, hallucinations, mania, or delirium, while gangrenous ergotism leads to necrotic tissue.

In her landmark paper in Science, Caporael was the first to suggest that the Salem Witch Trials were caused by contaminated grain. The more the villagers of Salem ate bread that had been baked using grain stores from the 1691 harvest, she argued, the more they ingested the toxin and then experienced its side effects — including hallucinations

Caporael referenced the diaries kept by villager Samuel Sewall, who noted the wet and warm spring of 1691 progressed into a hot and stormy summer. For Claviceps purpurea, the conditions were pretty much ideal.

Caporael also contended the ergot ingestion was localized, meaning that not all the grain in the area was tainted and not all the villagers were under the influence. The majority of the accusers lived to the west of the village, or they took their grain supply from farmers who lived west of the village. Eight-five percent of the accused witches lived east of Salem, as did 82 percent of the people who supported their innocence. Ninety-three percent of the adult accusers, in contrast, lived on the east side of Salem. Juvenile accusers also followed the same pattern.

Caporael found the accusers’ behavior consistent with ergot poisoning. Convulsive ergotism impacts the nervous system, and the accusers were known to have fits and muscle spasms. They also had hallucinations that seemed very real to them, and felt very terrifying to the people who witnessed them. The hallucinations were later used as “spectral evidence” during the trials; some accusers testified to seeing witches in their hearths at home. Others reported that the supposed witches were vanishing from the witness stand only to reappear in the courtroom rafters.

“What happened there was a tragedy of extreme proportions and a community was destroyed for generations," says Caporael. "There was a great deal of shame going on,” Caporael says.

Read More: People Often Blamed And Executed Witches For Plague And Disease

An Ongoing Mystery

Jonathan Corwin House, also referred to as the witch house, where many believe examinations took place (Credit: Carrie A Hanrahan/Shutterstock)

Carrie A Hanrahan/Shutterstock

In recent years, other researchers have found support for Caporael’s theory. A 2016 article in JAMA Dermatology analyzed descriptions of the accusers’ skin legions. During the trials, the bodies of both the accused and accusers were examined to see if they had a “Devil’s mark,” a skin blemish that was supposedly a sign that someone had made a pact with the devil. The study’s authors saw similarities between these descriptions and gangrenous ergotism.

“Gangrenous ergotism has many forms as it develops," explains Leela Mundra, the study's lead author and a plastic and reconstructive surgery resident at University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. "It eventually becomes very dark, woody and hard. It goes through multiple forms before it gets to that point because the tissue is dying." In Salem, such skin exams (and the accusations behind them) had fizzled out by the end of 1692. The summer had been dry and the area experienced a drought, which wasn’t hospitable for ergot growth; the villagers soon began ingesting a new, fungus-free grain store.

Other witch trials, however, have also been attributed to ergotism. The Finnmark witch trials, for example, occurred in the 1600s in northern Norway. Hundreds of women were accused, and 92 burned at the stake for the crime of witchcraft. Ergot poisoning has also been suspected in several “dancing mania” events in Europe, in which masses of people danced randomly in the street for hours.

But even considering such historical examples, there's only so much we can know about ergot poisoning — and what really happened in Salem. Despite recent studies like Mundra's, there's no solid scientific consensus on what truly sparked the chaos behind the trials. At any rate, by the 1800s, scientists better understood ergot, and farmers learned not to mill the tainted grain. Incidents of ergotism poisoning became increasingly rare, and many people soon forgot it was once a deadly problem.

Read More: The Symbolism Behind What a Black Cat Means: Are They Really Bad Luck?

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

History of Massachusetts. What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?

U.S. Forest Service. Ergot: The Psychoactive Fungus that Changed History

American Society for Microbiology. From Poisoning to Pharmacy: A Tale of Two Ergots

Science. Ergotism: The Satan Loosed in Salem?

JAMA Dermatology. The Salem Witch Trials—Bewitchment or Ergotism

Economic Botany. The Witch Trials of Finnmark, Northern Norway, during the 17th Century: Evidence for Ergotism as a Contributing Factor

The Lancet. A forgotten plague: making sense of dancing mania