The problem: Scientists want to study our circadian rhythms, our bodies' internal clocks, and they can do so on the genetic level by examining how gene expression changes throughout the day. But ordinarily that would require sampling a person's blood or skin multiple times a day, an ordeal few of us would want to endure. The solution: hair. Makoto Akashi's team reports today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that hairs, be they from the beard or head, contain the telltale signature of RNA activity that shows when we humans are at our peak activity level for the day.

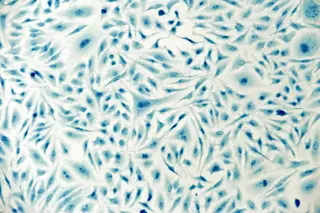

At the base of every strand of hair is a follicle of living cells, which clings to the hair when plucked. By tweezing an average of 10 head hairs per person (five for thick-haired folks and as many as 20 for those with thin locks), the researchers were able to isolate and track the activity of three separate clock genes. Beard hair was even more reliable: Just three strands produced accurate results. By plucking hair from four people going about their daily routines, the researchers found that peak gene expression (when the most transcribed RNA was present) matched peak wakefulness [LiveScience].

Akashi and colleagues didn't just grab tweezers and follow people around; they also used their volunteers to experiment. The scientists had the volunteers wake up later and later in the day, up to the point that they'd moved back their schedules by four hours. However, Akashi found, at the end of this three-week process, the people's circadian rhythms had moved forward only two and a half hours. Perhaps our body clocks are not as elastic as we might like. That was especially true for workers who frequently change shifts.

The team examined the hair follicles of volunteers who worked the 6 a.m. to 3 p.m. shift one week, the 3 p.m. to midnight shift the next week, and back to the morning shift on their third week. Clock gene activity lagged 5 hours behind the workers' lifestyles, the researchers found, which indicates that 3 weeks was not long enough for the body clock to adapt to the new schedules [ScienceNOW].

Related Content: 80beats: Ancient Ice Man’s Genome Sequenced via 4,000-Year-Old Hair

80beats: Rare Genetic Mutation Lets People (and Fruit Flies) Get by With Less Sleep

80beats: Night Owls Have More Staying Power Than Early Birds, Brain Study Shows

Science Not Fiction: Inception and the Neuroscience of Sleep

Image: flickr / johnath