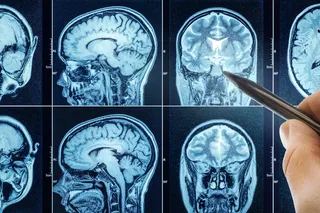

Drowsiness, dizziness and difficulties with balance, communication and concentration all count as common signs of concussions. So do fainting, sensitivity, slurred speech and – in some cases – seizures. With such a wide variety of possible symptoms, identifying and diagnosing concussions can be difficult. That said, a new device may make the process a bit simpler, particularly in the world of sports.

According to an article in Scientific Reports, researchers recently created a small sensor patch that attaches to the skin on the neck and measures sharp movements and sudden strains the second that they take place. The device could contribute to predicting the occurrence of concussions in certain activities (such as contact sports) and could inspire innovations in quickly diagnosing these traumatic injuries.

In some sports and activities – particularly those that involve close contact among participants – concussions are a constant. Any sudden collision, crash or sharp movement ...