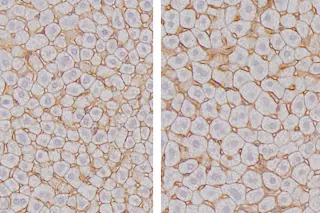

Mouse liver cells at the end of the day (left) and the end of the night (right) after they have grown. (Credit: Ueli Schibler/University of Geneva) Among all the organs in the human body, the liver is something of a superhero. Not only does it defend our bodies against the liquid toxins we regularly ingest, it has the ability to regenerate itself, and, as new research shows, it increases its size by nearly half over the course of a day. Working in mice, researchers in Switzerland documented this process of regular stretching and shrinking, watching as liver cells swelled in size and contracted up to 40 percent along with the mice's daily activities. There's a catch though, a kind of hepatological kryptonite. Their livers only exhibited this ability when the mice followed their normal cycles of eating and resting. They're nocturnal creatures, and if they began eating during the day ...

The Liver Grows by Day, Shrinks by Night

Discover how mouse liver cells growth varies day and night, highlighting the importance of cyclical liver growth in energy efficiency.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe