This article appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of Discover magazine as "Heart Ache." Become a subscriber for unlimited access to the archive.

Chloe looked miserable. She was curled up on the hospital bed, sweaty and shaking, wracked with waves of nausea, her heart racing. I gave her a cool washcloth and a basin as the nurse started her IV. I had cared for her before; though only 16, she’d been in the hospital a dozen times already.

“I think it may be another heart valve infection,” I told her. She nodded, familiar with the diagnosis, and the treatment that followed. She was at particular risk for a type of infection called endocarditis, where bacteria invade and infect the valves of the heart.

Chloe was born with an aortic valve that had only two parts, instead of its normal three, and was unusually small and stiff. As she grew older, her valve became thicker and less pliable. Unable to open properly, her heart had to work too hard to pump out blood. When she was 14 years old, surgeons cut through her breastbone to her heart, delicately repairing the abnormal aortic valve. Though her valve was now working normally and heart pumping well, she was still dealing with the procedure’s unwelcome consequences.

As before, we followed the same routine — strong antibiotics to kill the bacteria in her heart and bloodstream, fluids and medications to quell her nausea and dehydration. She settled into her hospital room with magazines and movies, expecting a long stay.

The Night Shift

Two days later, I stopped to check on Chloe at the beginning of my night shift. Her thin frame was tangled in the sheets, shaking and agitated, unable to find a comfortable position. Her nurse told me Chloe seemed no better — and perhaps worse — than when she’d arrived. The usual medicines did not seem to relieve her nausea, and she had started having diarrhea.

I wondered if something more was going on. Could it be a more aggressive or resistant bacteria causing her endocarditis, or an entirely new intestinal infection caused by her antibiotics? But blood tests showed the same common bacteria that had caused her previous heart infections, and which her antibiotic should kill. Stool tests sent that day showed no dangerous bacteria. Perhaps she just needed more time to improve on her current treatment.

As I sat by her bedside, I noticed a few other odd symptoms. Her pupils were as wide as saucers, her nose was running, and her skin was damp with sweat and covered with goosebumps. This constellation of findings pointed in a surprising direction that I had seen before in my adult medicine rotations as a student — opiate withdrawal.

I looked in Chloe’s chart, reviewing the medications she took routinely at home and those we had given her in the hospital. While she had needed opiate pain medicines such as morphine, hydrocodone and fentanyl in the past, we had not given her any this time, nor did she have any recent prescriptions for them.

Returning to her bedside with another cool washcloth, I approached Chloe gently. I asked her to be honest with me, explaining that I truly needed to know everything that was going on so I could help her out of this misery.

Tearfully, she began to whisper about her struggle with opiates, which had started shortly after her surgery. Despite trying, she had been unable to wean off the pain medications, finding herself dependent on the high they provided. She started buying oxycodone pills from a schoolmate at first, but when this got too expensive, she turned to a cheaper and riskier alternative: heroin. At first, she snorted or smoked it, but in the last several months had turned to injecting it. I realized this was likely what caused her endocarditis; the unclean needles introduced bacteria into the bloodstream, where they could nestle into her healing heart valve. Her days in the hospital restricted her access to opiates, sending her plummeting into withdrawal.

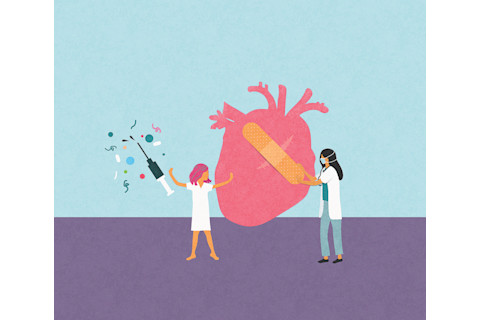

(Credit: Kellie Jaeger/Discover)

Kellie Jaeger/Discover

While not fatal, opiate withdrawal feels awful. Taking opiates generally slows things down, making you sleepy, constipated and slowing your heart and breathing rates. But withdrawing from them speeds things up, making you more agitated, with a faster heart rate and overactive bowels. For chronic opiate users, the first few hours without the drug are marked by cravings, anxiety and restlessness. Within a day, the body is wracked with tremors, insomnia, runny nose, profuse sweating, belly cramping, vomiting and diarrhea.

Now we knew we didn’t just have to treat Chloe’s endocarditis, but address her opiate dependence, as well.

An Ongoing Epidemic

Chloe was not alone; teens in the United States are using opiates at concerning levels. Between 2001 and 2014, opiate-use disorders among youth aged 13 to 25 soared nearly sixfold. Although their use has since started to decline, hundreds of thousands of adolescents still misused pain relievers each year between 2015 and 2019, according to a national survey from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

About a third of people over age 12 get their drugs from healthcare providers, at least initially. Opiates such as morphine and fentanyl can be immensely helpful for the acute, severe pain caused by surgeries like Chloe’s heart valve repair. These medications take advantage of our body’s natural pain response system. Under stress, our body can create its own pain management hormones, commonly called endorphins, sending chemical messengers that connect with opiate receptors in organs all across the body. The opiates we take as medications bind to these same receptors, mimicking endorphins. When bound to receptors in the brain and nerves, opiates quell pain signals, calm stress responses by dampening our “fight or flight” hormones and stimulate our brain’s reward and pleasure centers. These intoxicating effects on the brain are what give chronic opiate use the particular potential to develop into full-blown addiction. Outside the nervous system, opiates can slow down the intestines, disrupt deep sleep and blunt the body’s immune response. They can also cause the lungs to breathe slowly and irregularly, which is often the cause of death from overdose.

Studies show that 5 to 7 percent of adolescents and young adults prescribed an opioid will go on to develop an opioid-use disorder. Accordingly, all who care for teens must be wary of their potential to spark dependence. They can even lead to a more dangerous road — now, more teens are transitioning from prescription opioids to heroin, which is often less expensive and easier to acquire.

While adults are increasingly receiving care for opioid use disorders, for adolescents, the rate of treatment is actually declining, particularly among youth of color. It’s often harder for teens to get successful treatment because many care facilities are uncomfortable with or inexperienced in treating them. Those that do accept teens may find it difficult to keep them in treatment. And many providers who care for adolescents are uncomfortable or unfamiliar with the use of effective medications such as naltrexone or buprenorphine.

Thankfully, Chloe was open to treatment and had access to care from our hospital’s adolescent addiction team. She was given methadone during her hospitalization, which quickly quenched her withdrawal. Within weeks, her endocarditis was cured, and she left the hospital with a plan for tackling for her opioid-use disorder: She started taking methadone daily to address her body’s cravings for opiates. To deal with the psychological effects of her dependence, she began attending weekly counseling and group therapy sessions. Tired of spending time in the hospital, Chloe was driven to put her surgery — and all its complications — behind her.