Robert Hare steps out of the sunlight and into a West Vancouver pub. “Let me see your eyes,” says the 82-year old, piercing me with a cautious gaze that has sized up hundreds of criminals, including some of Canada’s most notorious psychopaths. The word itself has become a synonym for a certain type of evil, denoting a specific breed of cunning, bloodthirsty predator who lacks empathy, remorse and impulse control, readily violating social rules and exploiting others to get what he or she wants.

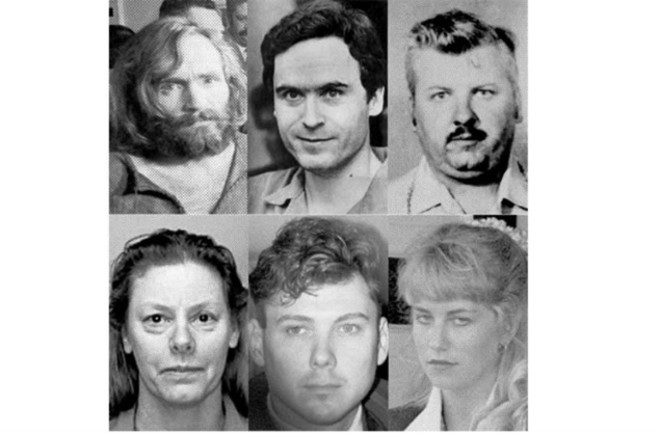

Psychopaths are capable of the most heinous crimes, yet they’re often so charming and manipulative that they can hide behind a well-cultivated mask of normalcy for years and perhaps their entire lives. Only the ones who get caught become household names, such as Ted Bundy, “Killer Clown” John Wayne Gacy and “Ken and Barbie Killers” Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka.

Hare’s oblique wariness of a reporter brandishing a voice recorder in a busy taphouse is perhaps no surprise, given his expertise with the subject and the research that suggests 1 in 100 people are psychopaths who tend to blend in, like cold-blooded chameleons. We know psychopaths make up 15 to 20 percent of the prison population, at least 70 percent of repeat violent offenders and the significant majority of serial killers and sex offenders. We know they’re difficult to treat using conventional methods, partly because they rarely seek out treatment. Yet they’re three times more likely to be released — and they get paroled almost three times faster — than their non-psychopathic counterparts. With the advent of neuroscience, we know the brains of psychopaths are atypical, leading some experts to call psychopathy a neurodevelopmental disorder, akin to autism, and one that’s diagnosable even in small children.

We know so much about psychopaths because of The Hare — officially the Psychopathy Check List-Revised (PCL-R) — the test that Hare developed for researchers in 1980 and released publicly in 1991. It’s now the gold standard used by researchers, forensic clinicians and the justice system to identify the hallmark traits and behaviors that make psychopaths chillingly unique.

With his leather jacket, silver goatee and circumspect gaze, Hare looks more like a retired detective than an emeritus academic. Ostensibly, he retired in 2000, when he closed his renowned psychopathy research lab at the University of British Columbia (UBC). But Hare remains an active researcher, developing new assessment tools, giving keynote addresses at conferences around the globe and holding workshops for forensic clinicians, prison staff and FBI profilers. Since his so-called retirement, Hare has spawned variations of the PCL-R to assess youth and children exhibiting early signs of psychopathy. He’s also turned his gaze on corporations. Finding that up to 4 percent of corporate staffers are psychopaths, he’s validating a research tool that HR departments and corporate staffers could eventually use to screen prospective and current employees, from mailroom to corner office.

What makes these people tick? How can we safeguard society against them? Perhaps most importantly, how are these predators spawned? Hare, known as “Beagle Bob” among his inner circle for his tendency to follow a scent, has devoted more than 50 years to wrestling with these questions, starting at a time when we didn’t even have a succinct definition for psychopath.

Among the Predators

The term was coined in the mid- to late 1800s from its Greek roots psykhe and pathos, meaning “sick mind” or “suffering soul.” In that era, the condition was typically considered a type of moral insanity. But that would start to change in the mid-20th century, when psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley published The Mask of Sanity, providing character portraits of psychopaths in his care at Georgia’s University Hospital.

Cleckley called psychopaths “the forgotten man of psychiatry.” He understood that many were violent criminals, but even repeat offenders tended to do only short prison stints, or they were released from psychiatric hospitals because they were diagnostically sane, displaying “a perfect mask of genuine sanity, a flawless surface indicative in every respect of robust mental health.”

Unfortunately, Cleckley’s rally call was largely ignored by the medical community. By the late ’60s, the bible of psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual(DSM), had replaced “psychopathic personality” with “antisocial personality disorder,” which still didn’t include hallmark psychopathic traits such as lack of empathy and callousness. This DSM classification endures today, yet while most psychopaths are diagnostically antisocial, the majority of people with antisocial personality disorder are not psychopaths.

Hare’s path into psychopathy research happened by chance and circumstance. He grew up in a close-knit family in a working-class suburb of Calgary, Alberta. Hare found school easy but had no clue what he wanted to do with his life. He liked math, science and archaeology, but he took a mix of courses at the University of Alberta, including psychology. By the late 1950s, he was completing his master’s degree in psychology. “I was curious about what drives our perceptions, emotions, motivations,” he says. “I wanted to know what was going on from an experimental scientific perspective.”

He met an undergrad named Averil in an abnormal psychology class. They married in 1959, and a year later, their daughter, Cheryl, was born. At the University of Oregon, Hare began a Ph.D. program in psychophysiology, a branch of biological psychology that studies the interplay between emotions, behavior and the nervous system. But when Cheryl had medical problems, they returned to Canada, where treatment would be more affordable.

In 1960, Hare took the first job he could get, as the psychologist at the British Columbia Penitentiary, a maximum-security prison on the outskirts of Vancouver.

“What did I know about working with criminals?” Hare asks while we wait for brunch to arrive. “I knew about the scientific constructs of psychology, not the clinical aspects, the laying hands on people part.”

Hare’s primary job involved assessing prisoners, using available tools ranging from personality tests to Rorschach ink blots, all of which were scientifically unreliable and, he’d soon discover, much less useful than the insights of prison guards. He was installed in a remote part of the prison, many locked doors away from the guards, making the panic button above his desk useless. Within the first hour, he encountered his first psychopath, an inmate he calls Ray.

“He was extremely predatory, looked at me like I was food,” recalls Hare. “With his eyes, he nailed me to the wall.” Then Ray pulled out a crude, handmade knife and waved it at Hare. When Hare refrained from pressing the panic button, Ray said he planned to use his weapon on another inmate. Hare felt that Ray was testing him, so he chose not to report the prisoner or the contraband weapon to other staff. Luckily, Ray didn’t carry out the threat, but Hare soon realized that Ray had snared him in a sort of trap, persuading him to forsake prison rules for clinical rapport.

Throughout Hare’s eight-month stint at the penitentiary, Ray persuaded Hare to endorse him for various plum prison jobs, including the auto shop, which led to a chilling send-off for Hare when he left to finish his doctorate degree at the University of Western Ontario. Hare brought his car to the shop for a tune-up just before his young family took their cross-country relocation trip. As they drove down a hill, the brakes failed. Luckily they made it to a service station, where a mechanic discovered that the brake line had been rigged for a slow leak.

Hare was relieved to escape to the academic world, now with an interest in studying the behavioral effects of rewards and punishment. He came across Cleckley’s book, and in these detailed character portraits, Hare recognized Ray, particularly his ability to charm and dupe otherwise sensible people. The inmate’s smooth-talking personality type had become a puzzle that Hare would devote his life’s work attempting to solve.

Making the List

In 1963, Hare returned to Vancouver and took a professorship at UBC’s psychology department. He hoped to conduct experiments into the biological responses to fear, phobias, motivation, rewards and punishment. At the time, UBC was a small regional school. The psychology department consisted of World War II-era army huts on the fringe of campus. Hare had no lab space, equipment or volunteers, so he called on colleagues at the BC Penitentiary and persuaded Correctional Services Canada to let him conduct risk assessment studies on the inmate population.

Hare’s first breakthrough psychopathy experiment measured physiological arousal. While hooked up to a sweat gland monitor, volunteers, all male, were told that they’d receive a brief shock eight seconds into a 12-second countdown. The study, published in The Journal of Abnormal Psychology in 1965, revealed that while most criminals and control subjects exhibited significant physiological stress in anticipation of the shock, psychopaths did not. In a similar study published the following year, participants were given the option to be shocked immediately or 10 seconds later. Eighty to 90 percent of non-psychopaths and community controls chose to get it over with immediately, but only 56 percent of psychopaths chose that option, suggesting that they did not mind waiting for an unpleasant event.

The results piqued Hare’s interest, but forensic psychology was in its infancy, and psychopathy research was virtually non-existent. “The literature on the topic was pretty barren,” says Hare. “Cleckley and I were two voices crying in the wilderness,” he says. “At times, I was ready to pack it in and go into archaeology. But I stuck at it.”

In 1970, Hare published the book Psychopathy: Theory and Research, attracting some attention in academia. “Good things began to happen,” he says. “I’d get batches of graduate students with great ideas. They revived me, and often they were the key study authors. I gave them free rein within their areas of interest, and the students really kept me going whenever I’d hit a plateau.”

By the mid-1970s, Hare had moved out of the barracks and into a rudimentary basement lab with that era’s cutting-edge equipment, including a 500-pound polygraph machine. His biggest hurdle became the lack of a valid assessment tool. Clinicians relied on the DSM’s loose construct of antisocial personality disorder and also self-report tests, which were easy for psychopaths to outsmart. Hare devised a checklist based on Cleckley’s key traits, but it wasn’t ideal. “Journal editors would say, ‘But what specifics go into an assessment of psychopathy?’” recalls Hare. “I needed something like the Richter scale for measuring the magnitude of earthquakes.”

Hare put his nose to the grindstone, analyzing data and conducting more prisoner interviews, with two independent assessors. Using psychometric measures, he weaned the list down from 100 to 22 items and in 1980, he published a paper describing his new instrument, the Psychopathy Check List. It immediately caught on with other researchers in North America and the U.K. “They might not have agreed with all the elements, but it allowed us to speak the same language and put all of us on the same diagnostic page,” says Hare. He and a core group of students made further revisions and by 1985, they had the PCL-R’s 20-item checklist, which boasted a high degree of interrater reliability, meaning that the majority of researchers agreed on the subject scores. “Its popularity exploded after that,” he says.

One Hare Lab study found that 80 percent of PCL-R-rated psychopaths reoffended within three years, compared with only 20 percent of non-psychopaths. Canada’s National Parole Board came knocking, wanting to test all prisoners. Hare had serious qualms about the potential misuse of the PCL-R outside controlled research settings, but after much deliberation, he sold the rights to a publisher in 1991. “The PCL-R was designed as a tool for pure research,” he says. “But pure research is more valuable when it has practical implications. We’re not operating in some academic vacuum.”

By the late ’80s, Hare was operating one of the biggest labs in UBC’s brand-new psychology building, staffed by 18 graduate and Ph.D. students, with custom soundproof chambers for electroencephalogram (EEG) experiments and financial support from a handful of government-sponsored grant programs. “Research was really humming along,” says Hare, who continued conducting groundbreaking experiments, including one testing Cleckley’s theory of semantic aphasia — “that the emotional components of language were somehow lost to the psychopath,” explains Hare. “For them, language is a purely a linguistic intellectual thing without the emotional underpinnings that color everything we do.”

The results piqued Hare’s interest, but forensic psychology was in its infancy, and psychopathy research was virtually non-existent. “The literature on the topic was pretty barren,” says Hare. “Cleckley and I were two voices crying in the wilderness,” he says. “At times, I was ready to pack it in and go into archaeology. But I stuck at it.”

While hooked up to an EEG that tracked brain activity, study participants looked at neutral or emotional words — table, desk, carpet, corpse, maggot, torture — followed by scrambled words. “With emotional words, most people can differentiate between words and scrambles very quickly, with high accuracy,” says Hare. “But psychopaths responded the same way to emotional and neutral words. There was no emotional turbo boost. That was stunning. In 1991, we submitted the paper to Science, and it was turned down at first because the editors thought these can’t possibly be real people.”

Science ultimately published the paper later that year, and it was replicated a few years later in the first-ever brain imaging study of psychopathy, a collaboration between Hare and the Bronx Veterans Affairs Medical Center substance abuse clinic.

As Hare drives us to his home near Horseshoe Bay, commenting occasionally on dangerous drivers exhibiting psychopathic traits, he points out that “scores of researchers doing MRIs have since replicated those early studies.”

Hare’s reputation for cutting-edge scientific research attracted many students to the Hare Lab, including Kent Kiehl, who completed his master’s and doctorate degrees there from the mid-1990s until the lab closed in 2000. “We discovered very striking differences between psychopath and non-psychopath brains,” says Kiehl, who has continued his research at the University of New Mexico since 2007. “But Bob taught me that it’s more important to listen to their stories and life histories. He’s interviewed some of the most notorious psychopaths in Canada. That makes him unique. Eighty percent of the researchers in psychopathy, some of the biggest names, have never actually met a psychopath. They haven’t spent time with the material, if you will.”

The 46-year-old Kiehl is executive science officer at the Mind Research Network forensics lab, which travels to local prisons with a mobile fMRI machine, tracking blood-flow changes while subjects are exposed to neutral and violent words and imagery. So far, Kiehl has assessed more than 5,000 brains and found that psychopaths have functional and structural anomalies that affect emotions, impulse control and cognition, leading him to view psychopathy as a neurodevelopmental disorder — a belief he shares with a number of other researchers and psychologists.

Neuroimaging is now increasingly used in the courtroom, including at a 2009 death penalty trial for Brian Dugan, a Chicago prisoner already serving a multiple murder sentence and who was later convicted of the 1983 rape and murder of a 10-year-old girl. Kiehl was hired by the defense to assess Dugan with the PCL-R and a brain scan, to convince the jury that the convict with an IQ of 140 had a neurological disorder that made him not criminally responsible, as is already the case for people with low IQ (a neurological disorder that qualifies for ineligibility for execution in nine states). Kiehl doesn’t know whether the brain scan and the accompanying PCL-R psychopath label impacted the jury’s ultimate death penalty conviction. (A year later, the death penalty was abolished in Illinois.) But like his mentor, Kiehl believes that brain scans could be just as common in the courtroom as DNA, as long as the information is conveyed by credible experts.

“I think that brain scans will one day be routinely used to categorize psychopaths and become standard fare in court trials. They’ll be just as revolutionary as the use of DNA evidence,” contends Kiehl, citing his recent study on impulsivity — “that brain scans were better than the PCL-R at predicting that psychopath offenders were four times more likely to reoffend.”

Hare is wary about the impact of brain scans in the courtroom. “Neuroscience is sexy right now, and brain scans are attention-grabbers,” he acknowledges as we sit on his balcony drinking cappuccino. “There’s some dramatic new stuff showing there might be anomalies in the cells between the frontal cortex and the limbic system, referred to as ‘potholes’ along the neural tracks. It’s interpreted as evidence of some sort of disconnection between frontal and limbic regions.”

But as Hare points out, “we don’t even know what the variations of a ‘normal’ brain look like. It might turn out that psychopathy is causally associated with functional and structural deficits, but for now the jury is out. We still have a lot to learn.”

Evil, or Evolution?

Even though there’s an abundance of scientific research on psychopathy, perhaps more than with any other personality disorder, specialists still can’t agree on the specific origins. “The majority interprets anomalies in brain structure and function as a cause-effect relationship,” says Hare. But some researchers think nurture trumps nature, and they equate it with early abuse and trauma.

“That’s part of the picture,” acknowledges Hare. “It’s just as reasonable, and more so in my mind, to interpret psychopathy as a developmental evolutionary thing,” he says, citing work by psychopathy specialists at Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care, a clinical and forensic hospital in Penetanguishene, Ontario.

“They argue that psychopathy is not a disorder; it’s what they call ‘an adaptive lifestyle strategy,’ ” says Hare. “You can pass on your genes by having one or two children and investing a lot into their well-being. But we know psychopaths’ relationships are impersonal, that they favor the strategy of having a lot of children, and then abandoning them.”

This biological adaptation theory qualifies psychopathy as an advantageous, albeit deplorable, method of genetic reproduction, not as a neurological disorder.

Both etiology theories could have serious real world implications. Could children be vilified as bad seeds or given special resources or medical treatment? Could workers be tested for psychopathic tendencies by employers? Could criminals be imprisoned for life based solely on brain scans?

“These are big issues,” acknowledges Hare, who now fields questions about neurological comparisons between psychopathy and autism at every talk he gives. “I don’t think psychopaths have a more primitive or a more evolved brain. . . . Nature provides for all sorts of diversity — that’s the point, isn’t it? We have some super-empathetic people and if a fly dies, they feel remorse — one extreme. The other extreme may be the psychopath. Most of us are somewhere in-between.

“From an evolutionary psychology perspective, the structure and functions [of psychopaths’ brains] may be a little different, but they’re properly designed for engagement in predatory behaviors. They could be genetically programmed, but what trigger mechanisms might set genes off? We don’t know. But we know that environmental factors are also a determinant,” says Hare.

Whether the debate is settled soon or not, Hare thinks we need therapy programs designed for psychopaths, including ones for children who are too young to bear the psychopath label but have callous-unemotional traits, alongside conduct disorder behaviors like fighting, bullying and stealing. “But you have to be very careful with labels and treatment. Psychopathy might not be so disordered and unnatural; it’s something that we can probably work with, help them take advantage of and shape in a way that’s pro-social and productive, good for the individual and society.

“My view is that psychopaths have the intellectual capacity to know the rules of society and the difference between right and wrong — and they choose which rules to follow or ignore,” says Hare. “They might even consider themselves more rational than other people. A psychopath I met in my research once told me that using his head instead of his heart gave him an advantage. He saw himself as ‘a cat in a world of mice.’ ”

After all these decades, Hare claims he’s often no better than the next person at identifying a psychopath, and that helps explain why he periodically eyeballs the proverbial windows to my soul. I ask Hare about the root Latin definition of psychopathy, which means a sickness of the soul. “People will say the behavior is pure evil, but what does that mean?” wonders Hare.

“I’ve never used these terms. Psychopaths can be dangerous and cause very serious problems in society. But I don’t know what the soul is. I think a better word is conscience, but what is that? Is it the concept of self-awareness? Can a computer think in this kind of abstract sense? I don’t think so, but maybe we’re also just a bunch of algorithms. It’s a mystery of human nature that makes my head hurt.”

Journalists have beagle traits, too, so I return to the question of what attracted him to specialize in such dark matter? Was it like an archaeologist discovering a new world?

“OK, sure, that sounds good,” he allows. “It’s funny to think that on my tombstone, it’ll say I was the developer of the PCL-R. This is my claim to fame? Do you know that Heimlich did a lot of basic science research? No, you just know the Heimlich maneuver.”

The Hare’s Breadth

The PCL-R — or The Hare, as it’s colloquially known — measures a constellation of 20 personality traits and behaviors. An accredited clinician, ideally one with a background in psychopathy, conducts a semi-structured interview with a subject, coaxing out information about the subject’s personality, lifestyle and personal history. The feedback is combined with information from the subject’s file and ideally interviews with family, friends, employers and other associates, to help the clinician determine whether the subject is evasive or deceptive.

The checklist’s 20 items include glibness/superficial charm, grandiose sense of self-worth, need for stimulation/proneness to boredom, pathological lying, conning/manipulation, lack of remorse/guilt, shallow affect, callousness/lack of empathy, parasitic lifestyle, promiscuous sexual behavior, early behavior problems, lack of realistic, long-term goals, impulsivity, failure to accept responsibility, many short-term marital relationships, juvenile delinquency and criminal versatility.

The clinician scores each item with 0 (no presence), 1 (uncertain) or 2 (definitely present). Psychopaths score 30 to 40 points. The general population typically scores less than 5, while the average score for prisoners is 23.

Since its inception, the checklist has remained the same, but the PCL-R manual has grown from a small pamphlet of just a few pages to the current 200-plus-page book packed with statistical data from psychopathy specialists around the globe. It’s now the top violence risk assessment tool used by forensic psychologists in North America, the significant majority in post-sentencing and parole hearings of the most dangerous, high-risk prisoners.

This article originally appeared in print as "The Psychopath & The Hare."