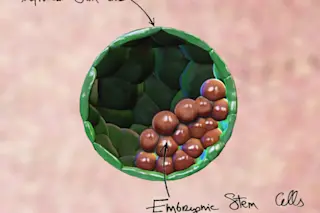

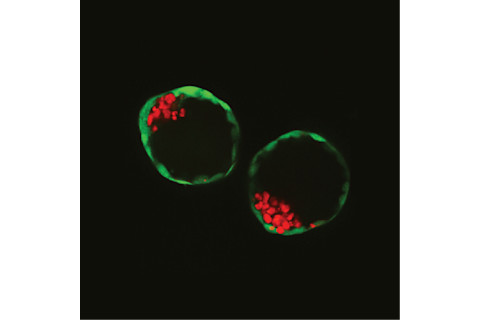

A representation of a blastoid, which is a synthetic embryo formed in the lab, from stem cells. The green cells are the trophoblast stem cells (the future placenta), whereas the red cells are the embryonic stem cells (the future embryo). (Credit: Nicolas Rivron) Studying human development — especially the earliest stages of pregnancy — can be a tricky thing. Usually, scientists need embryos to examine these early stages. The problem is, embryos are an expensive, limited resource and working with them is fraught with ethical dilemmas. Now, a new study in Nature details the development of a synthetic embryo that can help researchers avoid these issues and better understand the earliest days of development.

In the Beginning

First, let’s start with some basics. All embryos, at least in mammals, begin as blastocysts — structures made up of an internal cavity that contains a small cluster of embryonic stem cells, and an outer layer of stem cells called trophoblasts. These inner embryonic cells go on to form, you guessed it, the embryo, while the trophoblasts eventually morph into the protective placenta that surrounds the embryo. In the past, researchers have created stem cell lines for both embryonic cells and trophoblasts. This has been great for growing large numbers of the cells to study and use in experiments, since they mimic some stages of cell development. But there hasn’t been any comparable stem-cell model for the actual blastocysts made up of these cells. So Nicolas Rivron, a tissue engineer and developmental and stem cell biologist at the MERLN Institute for Technology-Inspired Regenerative Medicine at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, and his team set out to make one.

A New Model

The group took mouse embryonic stem cells and trophoblast stem cells and reintroduced them under specific conditions in the lab. When they did so, the two cell types spontaneously organized into synthetic embryos — so-called blastoids. In fact, the blastoids are so similar in shape to actual embryos that you can barely tell them apart under a microscope, according to Rivron. Better yet, the cells started communicating, changing the blastoids’ gene expression so they closely resembled embryos on a genetic level, as well.

A picture of two blastoids, which are synthetic embryos formed in the lab, from stem cells. The green cells are the trophoblast stem cells (the future placenta), whereas the red cells are the embryonic stem cells (the future embryo). (Credit: Nicolas Rivron) “This is actually kind of the moment where we said okay, we have a very good morphology, it really looks nice, but what about the genes?” Rivron says. “And when we saw the shift in gene expression, we said, okay, we have something here.” The team then put the blastoids to the ultimate test: transplanting them into the uterus. When a natural embryo implants successfully in the uterus, you see the mother’s (in this case, a mouse) uterus start to react, with blood vessels linking up with the embryo, flooding the implantation site with blood. “All these events were very clearly happening when we transferred the synthetic embryos,” Rivron says. Despite these successes, he emphasizes blastoids are not the full equivalent of embryos. Yes, they’re very similar in shape and gene expression, but they’re not identical; they’re actually slightly less organized than the real thing, and would never actually grow into a viable fetus. Still, the applications of having a model like this are exciting. Researchers can create huge numbers of these blastoids in the lab to study the mechanisms of early embryo development. Dissecting these stages in more detail can help experts better understand, for example, why couples undergoing fertility treatment aren’t seeing success in their embryos implanting. It could even help teams develop better methods of contraception. “For the first time, we can really study those processes that are occurring at the time of early development,” Rivron says. “And this has hardly been possible until now.”