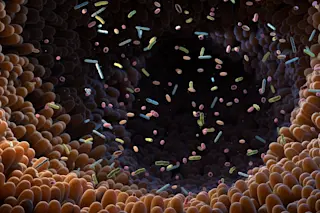

Nearly half of us are natural methane producers. That's because some people’s gut microbiomes include methanogens, microbes that produce methane as a byproduct of digestion. While this doesn’t mean we’re contributing to climate change in the way that cows do, it turns out that these microbes might be beneficially influencing something closer to home: how we digest our food.

A new study from Arizona State University, published in The ISME Journal, found that people with methanogens in their gut may extract more energy from a high-fiber, whole-food diet than people without them.

“That difference has important implications for diet interventions,” said Blake Dirks, lead author and graduate researcher at ASU’s Biodesign Center for Health Through Microbiomes in a press release. “It shows people on the same diet can respond differently. Part of that is due to the composition of their gut microbiome.”

Our gut bacteria play a major role in ...