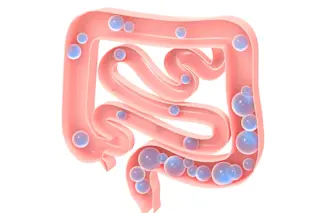

More than 400 different kinds of bacteria live in our intestines, forming a complex, microscopic ecosystem that helps us with everything from making and absorbing vitamins to digesting food. But surprisingly little is known about how this microscopic menagerie interacts with our bodies. Recently, three researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis found convincing evidence that some of these bacteria may actually communicate their needs to our intestinal cells, causing the cells to churn out sugars that the bacteria then eat.

Molecular biologists Per Falk, Jeffrey Gordon and graduate student Lynn Bry began their study by working with a line of mice raised for generations in a germ-free environment so their intestines wouldn’t carry any bacteria. They found that shortly after birth, the germ-free mice produced a carbohydrate that contained the sugar fucose. As the mice matured in the sterile environment, though, they stopped producing the sugar.

...