What’s the News: While mice are a major tool for biomedical research, they’re not always useful for testing the toxicity of pharmaceutical drugs because their livers don’t react to drugs the same way that human livers do. But in a new study, published in the journal PNAS

, scientists at MIT have gotten around this issue by implanting mice with miniature, humanized livers. Researchers may be able to use the artificial organs to help create drugs for diseases like hepatitis C

, which mice don’t normally contract, and improve the development of other drugs. "In the near term, we envision using these mice alongside existing toxicology models to help make the drug development pipeline safer and more efficient," said MIT biomedical engineer Alice Chen (via LiveScience

). How the Heck:

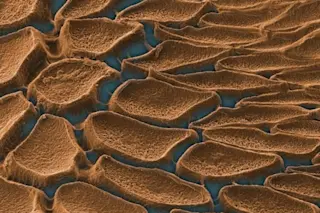

The MIT team first developed tissue scaffolds that are the same size, shape, and texture of contact lenses. In the ...