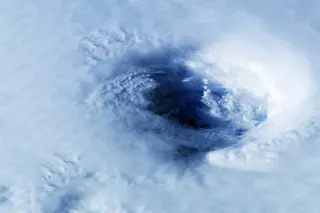

On a rainy day in July 2019, Michael Prior-Jones spent eight hours slip-sliding across a Greenland glacier. To help a colleague test the conditions deep beneath the ice’s surface, he played an intricate game of cat’s cradle with over 3,000 feet of wire cable. Pacing back and forth, he placed the cable on the ice to smooth out tangles and attach sensors that help indicate the speed at which the glacier is melting and moving toward open water. By the end, he was cold and soggy, but the wire was snarl-free and prepped for its descent into the glacier. Now, the real work could begin.

For decades, researchers like Prior-Jones have affixed instruments to cables, dropped them down cracks and boreholes, and analyzed the data that streams back through the wires. By extracting secrets from the depths below, scientists aim to understand the channels that meltwater carves on its way ...