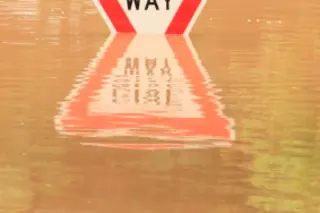

“The river came up to right where we’re sitting, and the waters were more than two feet deep,” Peter Goodwin tells me in the driveway of his ranch-style house perched on the banks of the Balonne River in St. George, a village of 3,500 in eastern Australia. It is a drizzly Sunday afternoon in April, three months after a devastating flood that drenched a landmass the size of France and Germany combined and isolated the town after the rain-swollen river rose to a record 45 feet.

Agricultural areas like St. George were hardest hit by the relentless rains and overflowing rivers that swamped roads, cut off power lines, washed away vineyards and fruit orchards, drowned thousands of head of cattle and other livestock, and covered homes and everything inside them in thick layers of sediment and mud. Shell-shocked residents are still digging out from under the debris.

“That’s the hard part of the flood—the aftermath,” says Goodwin, 60, a crusty, compactly built man with piercing blue eyes and calloused hands who works as an operations manager for the local municipality and has been staying with his grown daughter while he makes his home habitable again. “You get a lot of help during the flood, but then everyone settles back into their routine. There are a lot of houses down there that are still empty,” he adds, gesturing toward the riverbank. “And they will be for a long time to come.”

Everywhere I travel down under, the stoic Aussies are industriously patching together their shattered country, which has been walloped by one weather-related disaster after another. On an overcast Monday morning, I’m 200 miles east of St. George, cruising toward Brisbane, a sophisticated coastal city of more than 2 million, when I hit traffic that’s backed up for miles on the two-lane blacktop that crosses Cunningham’s Gap. Construction crews are still repairing the flood-related destruction on this highway and other roads throughout much of eastern Australia. A line of passenger cars, along with the brawny pickups favored in rural areas and the aptly named “road trains”—the double-trailer 16-wheelers that ferry cotton, apples, grapes, peaches, pears, and other produce to the coastal cities—inch down the steep grade, stuck in the kind of slow-motion gridlock that would normally send tempers flaring and horns blaring. After almost an hour in that slowdown, steam is coming out of my ears, but the other drivers seem to accept the jammed roads with a remarkable equanimity, looking upon them as simply another step in the process of recovery.

Australia has always been a country of climate extremes, but lately the swings of wet and dry have been shockingly intense. Weeks of torrential rains at the end of 2010 and beginning of 2011 (summertime down under) created tsunami-like waters that covered most of the province of Queensland. Then in mid-January, a cloudburst from a freak storm caused the Brisbane River to overflow its banks. A surging wall of water gushed through the pocket parks and tree-lined streets of downtown Brisbane, saturating trendy boutiques, stately government buildings, and gleaming glass skyscrapers.

As the waters advanced, thousands of people evacuated their homes and businesses. Panicked shoppers emptied supermarket shelves. With most roads closed, fleeing residents jammed an open highway in a frantic exodus reminiscent of the chaos on arteries leading out of New Orleans when the twin disasters of Katrina and the breached levees filled that city like a bathtub. Choppers crowded the skies ferrying supplies and rescuing stranded residents off rooftops. Lines for sandbags stretched outside relief centers, which were filled to capacity with people left homeless, and troops trucked in fresh food, water, and emergency supplies to a city the size of Houston.

The flooding claimed 35 lives and left more than 100,000 people homeless. The waters destroyed food crops, pushing prices of staples like bananas to $7 (AUD) a pound and decimating vineyards. Even the country’s lucrative coal mining industry was brought to a standstill. Damage came to an estimated $20 billion overall.

Less than three weeks later, nature struck again. In February, Cyclone Yasi, a Category 5 storm with a 300-mile front and winds gusting up to 180 miles an hour, roared in from the Coral Sea and slammed into Australia’s northeastern coast, flattening several beachfront towns still cleaning up from the floods. The largest cyclone to hit Queensland in nearly a century, Yasi forced thousands of people to flee Cairns, a steamy tropical paradise of 160,000 (think Miami Beach in the 1950s, but without the movie stars). Parts of the city were without power for five days; hospitals were emptied and patients were airlifted 1,000 miles south to Brisbane. Many villages along the coast, as well as the banana and sugar plantations, were left in shambles. From the air, the coastline looked as if a pack of 3-year-olds had gone on a rampage with Tinker Toys.

Australia is often called the lucky country. It is flush with natural resources—uranium, coal, oil, gold, and the rare earth minerals that are used in cell phones and electronics—and blessed with sparkling, pristine beaches that extend thousands of miles. It is home to some of the world’s oldest rainforests, lush tropical jungles with dense canopies that cover the northeastern tip of the continent. It is also a spacious country, almost as large as the continental United States, but with a population of just 22 million, smaller than that of Texas. About half of those people are clustered in three major cities that hug the eastern coast: Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane.

But the floods of the past year hint at a new, less fortunate chapter in Australia’s history. On many fronts, Oz is a land under siege. A changing climate seems to be intensifying the long-standing cycle of drought and flood—a state of affairs that could magnify the gap between the continent’s soggy coasts and arid interior in the future. In addition to the flooding, recent years have brought record heat waves, costly crop losses, and brush fires of unimaginable ferocity. As the planet heats up, these events are expected to become more frequent and severe.

Australia exemplifies what global warming models have long predicted, climate experts say, and what is happening in this hardy nation offers a glimpse of some of what is on the horizon for the United States as well. Rising temperatures tend to produce more extreme weather events, according to the models. “Our recent extremes may be strongly climate change–driven,” says Penny Whetton, a climatologist with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), Australia’s national science agency, in Victoria. “They’re an illustration of what we expect to see more of in the future, when natural fluctuations are intensified by global warming.”

With warmer temperatures will come more floods like the ones that have buffeted Australia over the past year, but the other half of the climate equation is making itself abundantly felt as well. During the past decade, much of Australia was gripped by a fierce dry spell that sparked stringent water rationing measures throughout the southern and eastern parts of the country. Evening news shows regularly announced water levels in the nation’s reservoirs and featured stories about scofflaws being slapped with heavy fines after neighbors caught them hosing down their cars. In one celebrated incident, South Australia’s water minister quenched his thirsty lawn in flagrant defiance of the rules, triggering a public outcry.

Adelaide, the driest major city in the world’s driest inhabited continent, came close to running out of drinking water in 2009, and officials were days away from importing bottled water for some of the area’s million-plus residents. Farmlands in the once fertile Murray-Darling Basin—a region in Southeastern Australia the size of France and Spain combined—were turned into cracked dust bowls. More than 10,000 families, many of whom had farmed for generations, were forced off the land. Power plants were shut down for lack of cooling water. Record heat waves baked the soil, killed wildlife, and turned the bone-dry terrain into kindling for firestorms that incinerated entire towns.

Australia prominently wears the scars of these escalating skirmishes with nature. The nation’s capital, Canberra, is a parklike planned city of nearly 360,000 that occupies a patch of land partway between Sydney and Melbourne, with wide, tree-lined boulevards that radiate outward from Lake Burley Griffin. Yet today, an aerial view reveals huge swaths of the countryside surrounding Canberra blackened from a firestorm that threatened to engulf the city in 2003, after months of scorching weather turned pine forests into a giant tinderbox.

About 20 miles outside Canberra is the Googong Reservoir, a long finger of water that stretches more than 650 acres when filled to the brim. More than a million people get their drinking water from the reservoir, but the drought shriveled it to less than 30 percent of its capacity. Even after the recent drenching rains, water levels remain perilously low.

Elizabeth Hanna, a public health researcher at Australia National University in Canberra, has a hard time reconciling another shrunken body of water, Lake George, with the shimmering sea of her youth. “When I was a child, we’d drive up from Melbourne and it would be overflowing its banks,” she recalls.

Some of Australia’s sensitivity to climate change stems from its evolution as a continent. Around 45 million years ago, the Australian landmass broke away from Gondwana, an ancient supercontinent that encompassed South America, Africa, and Antarctica as well. Almost completely covered in rainforest in those days, Australia then drifted northward toward the equator in complete isolation for 30 million years. During that period, the central regions of Australia dried out and created some of the world’s most ancient deserts.

Australian soils are deficient in vital nutrients including nitrogen, phosphorus, and zinc, mainly because the region is so old, even in geologic time, and most of the country has not been revitalized by the soil-renewing activity of volcanoes or glaciers for tens of millions of years. “The country is already dry and ecologically fragile, with relatively poor soils,” says Steven Sherwood, an atmospheric physicist and codirector of the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. “It doesn’t have the resilience, so it’s more vulnerable to anything.”

Modern development has exacerbated some of those vulnerabilities. River systems have been heavily exploited for irrigation, which has hastened soil degradation, made the ground saltier, and contributed to creeping desertification. And roughly 85 percent of the population is crammed into coastal cities that are susceptible to storm surges and cyclones. But the prime driver of Australia’s unique vulnerability is geographic: its location in the midst of three oceans, and the interacting currents that result.

Pacific currents have historically switched between patterns known as El Niño and La Niña, triggering correspondingly dry and wet years and perhaps decades. During El Niño, warmer waters in the southeastern Pacific create air pressure systems that drive rain out over the ocean, resulting in less precipitation over the continent itself. La Niña cools ocean temperatures, leading to stronger easterly winds in the tropics. All this causes more water to evaporate into the atmosphere, intensifying monsoon rains and cyclones. At the same time, the Indian Ocean Dipole, a current discovered only in the past decade, cools the eastern tropics and warms western currents, lessening spring rains in the southeast.

Rising global temperatures portend shifts in all these ocean currents, potentially with drastic consequences, says Albert Gabric, an environmental scientist at Griffith University in Brisbane. Some of the strongest El Niño patterns ever recorded were blamed for the crippling drought, while an equally intense La Niña brought on the downpours that inundated Queensland. Changes in the Southern Annular Mode, an ocean current that prevents low-pressure rain systems from passing over southern Australia, has helped shut off winter showers in Perth. Rainfall over this area has dropped by 20 percent.

Beyond these perturbations, there are worrisome hints that water is already tunneling away underneath the ice shelf in Antarctica. “Breaking up of glaciers in Antarctica will cool the surface temperature of the Southern Ocean, which in turn could make wind patterns more intense, causing more severe and frequent cyclones,” Gabric says. “There are multiple stressors, creating layers upon layers of complexity, and warming adds an extra dimension.”

To an American visitor, Australia feels like a parallel universe. Here in the United States, politicians and radio talk-show hosts regularly ridicule the notion of global warming and attack the integrity of climate scientists. Aussies, in stark contrast, have little doubt that they face increasingly stormy weather and are bracing for a bumpy ride. “You can’t live in this area and not realize what is happening to the land,” says Steve Turton, a physical geographer at James Cook University in Cairns.

In many ways, Australia is still grappling with how to respond to climate change. It is a coal superpower, the world’s largest exporter of the dirtiest of all fossil fuels. Australia relies heavily on coal for its own electricity as well, emitting more CO2 per person than any other developed country, and its agricultural emissions are among the highest per capita in the world, mainly because of the large numbers of sheep and cattle.

But a recently introduced carbon tax—a possible model for other industrialized nations—creates monetary incentives for curbing the use of fossil fuels and investing more in renewable energy. The Australian government recently invested nearly $500 million in climate change research, including $126 million specifically earmarked to identify the best strategies for adaptation to hotter days, storm surges, drought, and rising sea levels. Scientists are actively working on drought-resistant crops and farming practices, better ways to use and distribute drinking water, new firefighting strategies, and techniques for preserving Australia’s unique ecosystems and wildlife at an affordable price.

“We are between a rock and a hard place,” says Christopher Cocklin, senior deputy vice chancellor of James Cook University in Townsville. “We have an economy that is deeply reliant on fossil fuel resources such as coal, but we are getting religion. With the right amount of will and leadership we can certainly avoid the worst.”

Australians did take some convincing, though, especially since severe weather swings were already part of the country’s daily life. An emphatic 2008 report by economist Ross Garnaut, a former global warming agnostic who became, in his own words, “a late-life convert” to the green cause, did much to dispel any lingering questions among most Australians about whether the threat of climate change was real.

“There is a resistance in the emissions-intensive [industries] to change,” Garnaut said in a keynote speech at the Greenhouse 2011 conference held earlier this year in Cairns. “I understand the preference to wish it away. But if we do nothing . . . it will mean the end of civilization as we know it. We’ll be one of the species facing extinction.”

Fighting Fire With Fire

They called it Black Saturday: On February 7, 2009, after a decade-long drought and a suffocating heat wave, a firestorm of unimaginable ferocity swept through southern Australia’s farms and forests. Burning embers from the bark of trees were carried aloft by shifting winds and updrafts of the fire’s own convection currents for up to 20 miles, jumping across roads, clearing fire breaks, and starting new blazes on the parched ground. With flames shooting hundreds of feet into the air and temperatures reaching 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit, even the wet mountain ash forests were set ablaze.

At least 173 people lost their lives in the fires, which covered more than 1,700 square miles. Some died getting out of their cars in an attempt to outrun the fires or find shelter. Others stayed to defend their homes and farms and perished in the effort. Entire communities were ringed by flames. “When you have a lot of fires burning under these extreme conditions, there’s very little that can be done to control them,” says Andrew Sullivan, a bushfire researcher at CSIRO.

With rising temperatures and the specter of more extreme droughts, scientists like Sullivan are conducting controlled burns to shed light on the behavior of fires. They are using a device called a Pyrotron, an 80-foot-long fireproof aluminum wind tunnel with a glass observation area. An array of sensors inside the tunnel, one of the largest of its kind, can measure the combustion effects of wind speed, temperature, humidity, and different fuels such as leaves, twigs, grass, and bark. The goal is better prediction of a fire’s characteristics, from rate of spread to flame height to intensity, so firefighters can develop more effective countermeasures.

“We want to develop strategies to outwit fires and figure out benchmarks of how long it takes for them to become uncontrollable,” Sullivan says. “If we know that by the time a crew gets there, the fire is going to be beyond control, we’re better off dispatching resources somewhere else.”

A Watchful Eye Over Australia’s Water

Throttled by a water crisis that threatens Australia’s future, the Australian government in 2008 launched a $10 billion campaign that is radically transforming the way water is handled at every level, from allocations for agriculture to the faucet flow rate in Sydney high-rises. The effort could serve as a model for other water-starved regions in the United States and around the globe.

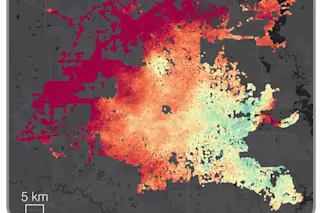

The Water Resource Observation Network (WRON), located on the leafy campus of Canberra’s Black Mountain Laboratories, is both the test bed and the nerve center for the campaign. Stuart Minchin, an environmental chemist and IT whiz who heads the WRON team, shows me around a climate-controlled room where hard drives the size of meat lockers corral information from the nation’s diverse water management agencies and track virtually every drop of water in lakes, reservoirs, aquifers, and river systems. “If we can’t measure it, we can’t manage it,” says the 41-year-old Minchin. He sports an earring in his left lobe and wraparound sunglasses atop his thinning corona of dark hair, but his casual demeanor belies his relentless drive to create the world’s most ambitious water information and accounting system.

Inside WRON’s enormous data facility, computer programs predict how the water supply will fare under different climate scenarios. On the basis of that information, Minchin and his colleagues are developing suggestions about where water should be allocated and how it should be used as the country’s water austerity plans become more stringent. Next the WRON team intends to deploy low-cost wireless sensors that can be embedded in waterways to feed data back continuously to the hub, allowing water resources to be managed in real time.

During the last century, the Australian government encouraged farming on difficult land, handing out water licenses to just about anyone willing to put in the backbreaking toil of making the country’s vast tracts of scrub desert bloom with citrus orchards and vineyards. The resulting irrigation demands eventually overburdened a poorly managed river system, which collapsed in 1998 when the drought hit. “We had successful farmers in desperate straits, forced out of business because they couldn’t get enough water to keep their trees alive,” Minchin says. “That was our Katrina moment. We had to develop a scientific basis for determining if these rights and entitlements are compatible with one another.”

WRON is just one strand of Australia’s response. “You need a portfolio of approaches in managing water security,” says James Cameron, acting CEO of the National Water Commission, the Canberra-based government agency in charge of the country’s water reform agenda. “The right mix will depend on what’s available in different parts of the country.”

The government imposed severe limits on water consumption, enforced by stiff penalties. Almost all households are now metered, and prices were nearly doubled on average to better reflect water’s true cost. Extensive public campaigns educated residents about how to conserve water: taking four-minute showers, installing water-efficient taps and toilets, recycling rain. Rainwater tanks and water-efficient showerheads became mandatory. Major cities cut their water consumption by up to 40 percent in the past decade, despite population growth. The government also earmarked more than $10 billion for water improvement measures, including more efficient farm irrigation methods and new pipelines that significantly reduce losses due to leaks.

Along with curtailing demand, Australia is increasing supply by drawing potable water from the ocean that surrounds the country on all sides. In 2006 its first reverse osmosis desalination plant opened in Perth. It now supplies 17 percent of that city’s drinking water, and similar plants are operational or under construction in Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, and Adelaide. Since reverse osmosis is energy-intensive, researchers are looking at cheaper ways to extract water from the sea as well.

The recent rains have at least given Australians some breathing space on water supply problems, Cameron says. “They provide us with a real opportunity to plan for the next inevitable drought.”

Engineering a Rainforest Rescue

The Daintree River ferry embarks from the southern bank, where spidery coral fingers of the Great Barrier Reef almost caress the shore. Across the way, a canopy of mist hovers over one of the world’s most ancient rainforests, an expanse of some 465 square miles that is more than 100 million years old. An hour’s drive farther north along the rocky coast, at the Australian Canopy Crane Research Station, which is part of the Daintree Rainforest Observatory, conservation biologists are studying the effects of changing climate on this primordial spot. Suspended high above the canopy, in a gondola hanging from a construction crane, they have unparalleled access to life at the top of the trees and a unique perspective on the forces that threaten this remote region.

In its rich biological diversity, the Daintree provides a living record of the evolutionary history of Australia’s plants and animals during the past 100 million years, as well as a window on its future. But gaining that knowledge has become an urgent affair. Temperatures in the region are expected to rise by an average of up to 3 degrees Fahrenheit within the next 20 years, and up to 10º by 2070. Such warming could disrupt or destroy much of the Daintree. “Once you get up around 1,500 feet, it’s almost exclusively ancient plants and animals that can’t tolerate heat, and they’ve got nowhere to go,” says Steve Turton, a climatology and rainforest ecology expert who helps manage the terrain.

Daintree is just one of the sites in Australia’s Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (TERN), an information-sharing organization that collects, manages, and shares data on flora, fauna, and other environmental factors to capture snapshots of what key wilderness ecosystems look like now and measure the potential effects of climate change.

Around the Great Barrier Reef, warming ocean waters are becoming more acidic, bleaching the coral and threatening the rich community of life drawn to the reefs. In 2005 the Australian government began setting up “green zones” in the reef areas and implementing new regulations to prevent overfishing, a strategy that has had some success. Alpine regions are under siege by weed and pest invasions, more fires, and reduced snowfall. As conditions get drier and hotter, plants and animals move to higher ground to stay cool but can quickly run out of mountain needed to survive. “We can’t save them all, but we intervene to help some adjust,” says Ary Hoffmann, who studies the effects of climate change on biodiversity at the University of Melbourne.

Here in the Daintree, keystone species play a critical role in maintaining ecological balance. Endangered cassowaries—colorful, turkey-size birds—eat many different kinds of fruits, the seeds of which travel through their guts before being excreted in fertilizing dung. Rescuing the birds by creating cassowary habitats helps preserve the habitat for everything else. The question now, Hoffmann says, “is can we help them mount an evolutionary response, and can they adapt in time?”

Farming Adapts to the New Climate

Simon Tickner and Susan Findlay Tickner couldn’t have picked a worse time to give up big jobs in Melbourne and move back to the farm his family has owned in southeastern Australia for more than 70 years. “That was in 1998, and we essentially walked into 12 years of drought,” Susan says. “One of the hardest things was watching our first crop die when the drought hit.”

Yet the Tickners adapted quickly, adopting a suite of strategies to manage the increasingly hostile land and turn a profit, even as farmers around them were in dire financial straits. Their shrewdest move was switching to no-till farming, in which seeds are planted without using a plow to turn the soil. Healthy topsoil and stubble—the foot or so of a plant left standing after the previous year’s crop has been harvested—act like a canopy of mulch, retaining both moisture and nutrients while preventing soil erosion, all with less fertilizer than before. By retaining carbon in the soil, no-till farming also reduces the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere.

GPS satellite navigation now guides the Tickners’ tractors, letting them plant seeds precisely between the rows of old standing stubble. A software system called the Yield Prophet helps them manage those crops and generate optimum yields, given different scenarios of seasonal rainfall and temperature. “We’re getting drier and more extreme weather, and there’s no doubt in my mind the climate is changing,” Tickner says. “Since we’ve been on the farm, we’re now planting at least four weeks earlier, and that is in just 13 years. People must be nimble. They’ll have to change and adapt to various conditions to succeed.”

More technological assistance is just around the corner. Mark Howden, head of agricultural climate adaptation projects at CSIRO in Canberra, oversees projects to develop new farming systems that reduce water seepage and new crops bred with genetic traits suited to hotter, drier conditions and elevated carbon dioxide. While these advances will also help large-scale agribusiness, they are critical to small farmers, who have less room to diversify if one crop fails. At the same time, CSIRO is also crafting lower-tech programs for farmers in nearby developing countries, which may face severe food shortages due to crop failures and even widespread famine as the weather heats up, water dries up, and population explodes.