Update (March 15): Shortly after this post was originally published, the situation at the Fukushima Daiichi facility worsened dramatically: there was an explosion at a third reactor, which may have damaged the containment unit there, along with a new fire. Reports elsewhere now suggests that more radioactive material escaped, but the extent of the risk of further release of radioactivity is not yet clear. The title of the post has been edited to reflect the changing situation. (Original title: "Relax: Fears Of Japan's Radioactive Leakage Are Overblown")

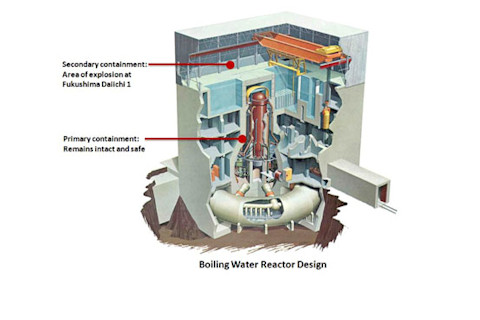

A second explosion hit Japan's Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant today and authorities are preparing to pump seawater into a third imperiled reactor. But considering that Friday's earthquake was seven times more powerful than the maximum limit they were designed to withstand, we're lucky the situation isn't much worse. Japan's scenario is a far cry from Chernobyl: Any radioactive leakage that has occurred is low, and unlikely to affect anyone outside the local area (if that). What Happened Both today's explosion (in reactor No. 3) and the one on Saturday (reactor No. 1) have the same cause: a breakdown in the cooling system as tsunami waters swamped generators. Specifically, today's explosion was caused by hydrogen gas, which builds up as the seawater that's pumped in to cool the reactor also heats up. From video footage, the explosion looks devastating, and while 11 people were injured, the steel and concrete containment shell around the nuclear reactor was not damaged---which is the main reason why authorities say the situation is mostly under control. "There is no massive radioactive leakage," Cabinet Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano told the New York Times. Here's a rundown on the risks in the leakage that has occurred: What Is Escaping (and How)? The root problem is heat: Even though the nuclear chain reaction is safely stopped in all of Japan's nuclear reactors, that doesn't stop heat from building up.

The uranium “stopped” the chain reaction. But a number of intermediate radioactive elements are created by the uranium during its fission process, most notably Cesium and Iodine isotopes, i.e. radioactive versions of these elements that will eventually split up into smaller atoms and not be radioactive anymore. Those elements keep decaying and producing heat. Because they are not regenerated any longer from the uranium (the uranium stopped decaying after the moderator rods were put in), they get less and less, and so the core cools down over a matter of days, until those intermediate radioactive elements are used up. [The Energy Collective]

The radioactive particles that are entering the environment are mostly planned escapes: Workers vent steam to release pressure as the reactors heat up the water. And while some report low levels of radioactive cesium and iodine, the majority are radioactive nitrogen, which don't pose much of a health hazard:

By the time you spelled “R-A-D-I-O-N-U-C-L-I-D-E”, they will be harmless, because they will have split up into non radioactive elements. Those radioactive elements are N-16, the radioactive isotope (or version) of nitrogen (air). The others are noble gases such as Xenon. But where do they come from? When the uranium splits, it generates a neutron (see above). Most of these neutrons will hit other uranium atoms and keep the nuclear chain reaction going. But some will leave the fuel rod and hit the water molecules, or the air that is in the water. Then, a non-radioactive element can “capture” the neutron. It becomes radioactive. As described above, it will quickly (seconds) get rid again of the neutron to return to its former beautiful self. [The Energy Collective]

So What's The Risk? We don't know exactly how much radioactive material has been released, but we do know that only very low levels have been detected around the plant.

The IAEA has described it as a level four event on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES), which is used for an accident "with local consequences". No abnormal levels of radiation have yet been detected in Russia. [BBC]

The radioactive nitrogen decays in seconds, and therefore seems to pose no threat. Other radiactive elements are not so innocuous:

Radioactive iodine could be harmful to young people in the vicinity of the plant. After the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster there were some cases of thyroid cancer as a result. People who were promptly issued with iodine tablets ought to be safe, however. Radioactive caesium, uranium and plutonium are harmful, but do not target any particular organ of the body. [BBC]

These iodine tablets help fight radiation by making sure your body has all the iodine it needs: With sufficient iodine levels, your body won't need to absorb any more, which in this case, would be radioactive iodine. According to Josef Oehmen, a research scientist at MIT:

There was and will *not* be any significant release of radioactivity. By “significant” I mean a level of radiation of more than what you would receive on – say – a long distance flight, or drinking a glass of beer that comes from certain areas with high levels of natural background radiation. [The Energy Collective]

Yet despite the low risk, tens of thousands of people have been evacuated around the plants for precaution, and the U.S. moved an aircraft carrier after it detected low-level radiation 100 miles offshore.

No Comparison to Chernobyl The reactors in Japan are built to a much higher standard than the ones that led to the 1980s Chernobyl incident.

At Chernobyl an explosion exposed the core of the reactor to the air, and a fire raged for days sending its contents in a plume up into the atmosphere. At Fukushima the explosions - caused by hydrogen and oxygen vented from the reactor - have damaged only the roof and walls erected around the containment vessels. [BBC]

In Japan, all nuclear chain reactions have been successfully stopped, and all the explosions occurred outside the reactors' containment vessels---so there is no major risk of significant radioactive leakage. What's Next?According to Oehmen, the normal cooling water will gradually replace the the seawater coolant, and like any nuclear reactor fuel change, workers will dismantle the core and haul it to a processing facility. But it will probably take five years to check the entire plant for damage, and with the inspection of its nuclear power station, Japan's power generating abilities will probably be reduced by about 15%---not nearly as bad what could have happened if the earthquake had damaged Japan's nuclear plants more seriously. Related Content: DISCOVER: Exactly What Happens to the Ground at a Fault Line? DISCOVER: Is the West Coast Ready for a Tsunami? DISCOVER: Waves of Destruction DISCOVER: The Next Big Quake

Image: The Energy Collective