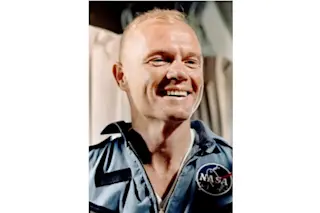

When NASA launched John Glenn on its first ever orbital mission in 1962, there was a pretty realistic chance that he was going to die. Not because the agency was taking an unnecessary risk. It wasn't; every element of the flight was tested and proven to a point where everyone, Glenn included, was confident. But still, it was the early 1960s and rockets had a nasty habit of blowing up.

With that in mind, a memo reached Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson on January 16, 1962. It was from O. B. Lloyd, director of NASA’s Office of Public Information, and it outlined exactly what would happen if Glenn was killed on his Friendship 7 mission. In considering what might happen to Glenn that would force a statement from NASA and the White House, death was top of the list.

The rocket could explode on the pad, some catastrophic failure could ...