The distinctions between ancient and modern whales are astounding. While whales once lived on land, their modern marine descendants are now skilled swimmers, amazingly well-adapted to the seas.

With such dramatic differences between their bodies and behaviors, it's no wonder that the transition between these two types of whales — ancient and modern — was a mysterious and prolonged process, taking place over several millions of years. And though scientists are still struggling to understand the transition as a whole, they're slowly and surely unraveling much of its mystery.

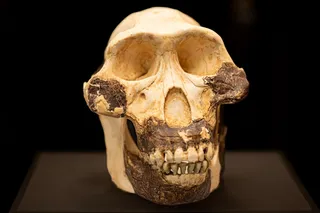

According to a recent research paper published in PLOS ONE, a newly identified skull and partial skeleton of a strange whale species revealed a new genus from the shallow seas of Morocco, approximately 40 million years ago. Representing a transition stage in between the most ancient and most modern whales, the researchers suggest that the members of this genus lived manatee-like ...