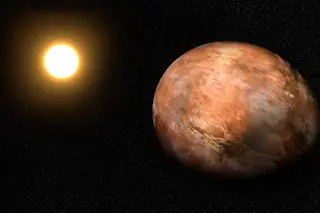

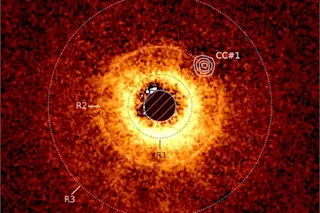

Stars wrapped in warm, dusty disks sound cozy, and in cosmic terms, they are. They are the incubators in which planets like our own — rocky, and fairly close to their parent sun — are most likely to form. In these disks, dust is coalescing and tiny chunks of rock are colliding to become larger masses of matter and, over the course of millions of years, planets. The theory is far from perfect, though, and computer models meant to simulate the process raise as many questions as they answer. Astronomers have lately tried to remedy that, watching dust-shrouded stars for any small changes — maybe a tiny shift in the amount of starlight making its way to Earth — that they can plug into the models to help make them fit reality.

Carl Melis, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, San Diego, and his collaborators chose one of ...