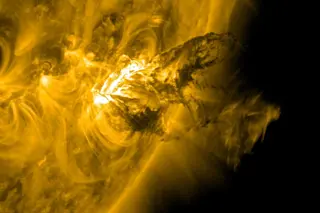

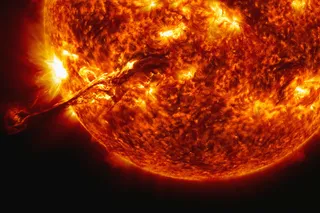

A closeup of a gargantuan eruption of plasma on the sun's surface on June 7 was captured by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory. Click on the image for a larger version. And check out the text and additional images below to learn what happened when the stuff splattered back down onto the sun's surface. (Image: NASA / SDO / P. Testa-CfA) On June 7, the sun belched and made a mess — to the great delight of astronomers. The gargantuan eruption blasted billions of tons of plasma burning at 18,000 degrees F into space. It's the dark filamentous stuff blasting out from the sun's lower right quadrant in the closeup image above, captured by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory. And when some of it landed back on the sun's surface, the resulting splatter gave astronomers insights that may help them gain a better understanding of how stars form. Check out this animation ...

Solar Belch: KaPOW! Spluuuurt! SPLAT!

Marvel at the solar plasma eruption captured by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, revealing cosmic insights into star formation.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe