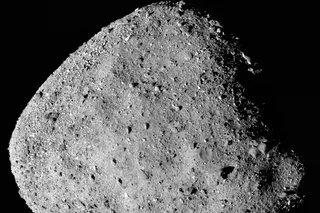

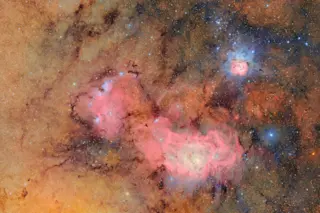

Sometimes there are second acts in astronomy. Perhaps you missed last November's dazzling Leonid meteor blizzard—or you watched it and got hooked. Either way, you'll have another chance to see shooting stars this month. For the first time since 1999, the Perseid meteor shower will unfold under spectacularly dark, moonless skies. And if you're under clouds the first peak night, August 11, you can catch a repeat performance the following night.Like the Leonids, the Perseid meteors are minuscule bits of comet crashing into our planet's atmosphere—petite cousins of the giant impacts that may have wiped out entire species in the past. "Just one comet in a million can hit Earth," says Kevin Zahnle, a planetary scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center. But each time a comet passes close to the sun, it evaporates a little and leaves behind a trail of debris. Those comet crumbs spread out over millions of ...

Sky Lights: Observing the Perseid Meteor Shower

What happens when Earth collides with a piece of comet? See for yourself!

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe